No one we know loves the sport of track and field more than Stewart Blue. He might have his equals, but no one loves it more.

And it's been that way for almost 60 years.

He was a standout high school track guy and even better in college ... and he has remained involved with the sport ever since, for decades now as a meet official, a timer, overseeing an event, as an umpire or as a referee.

So he knows the rules, he has to OK the disqualifications and he has to care ... and he does.

The tall man loves him some track and field, and appreciates its athletes.

If there is a meet at Texas A&M, he will be there. If there is a meet at LSU, count on Stu. The Louisiana high school state meets? He's missed only two since 1972, only because they conflicted with college conference championship meets to which he was committed.

|

| Stewart, with daughter Jamie and wife Karen. |

He loves his wife and his daughter, son-in-law and two grandkids, and he has a life. But track and field is, a part of his being.

A number of recent bouts with prostate and brain cancer have been hurdles to clear. But he's been hurdling since those early 1960s days at Byrd High School in Shreveport.

As a Byrd senior in 1965, he was part of the last state championship team for Coach Woodrow Turner, the last of nine top-class titles in a 12-year span. Blue finished second in both the high and low hurdles at the state meet.

He was a popular figure with competitors, open and friendly and garrulous, easy to spot (he's 6-foot-4) ... and talented.

He lives now, as he has for years, in Lafayette. But he also spends much time in Cut Off (deep on the bayou in southeast Louisiana; home of LSU head football coach Ed Orgeron). That's where daughter Jamie Blue Guidry lives with her family.

She is marketing director for the company that owned the plane that crashed in Lafayette last December on the day of the LSU-Oklahoma national semifinals football game, and Stu and his wife Karen have been in Cutoff to help with the two grandchildren.

And this year -- as with everyone else -- Stewart's track-field schedule was rudely interrupted. It ended with the SEC Indoor Championships before the pandemic hit.

But he’s looking ahead to 2021.

On the schedule — if conditions permit — are the SEC and NCAA indoor meets at Arkansas, the completion of his 45th year of meets at LSU, the Olympic Trials next summer as an umpire, and the referee job at the SEC Outdoor Championships at College Station in May.

For this article, however, we reflect and take a long look back.

---

Stewart credits Woodrow Turner and Scotty Robertson, two of his Byrd coaches — legends both — for giving him his greatest career boosts and motivation.

First, though, came a Robertson evaluation. After a week of basketball "games" and drills in a P.E. class as a sophomore in 1962, Stewart heard that basketball wasn't a fit.

Scotty's bad news: “He said that I couldn't walk and chew gum at the same time," Stu remembers. "The good news (for him) was that I would not a basketball player; that my name would be ’floor’ if I tried because I couldn’t jump off the floor.”

But Woodrow Turner, listening to that conversation, called Stu over to his desk.

“He started to flatter me, which was his norm,” he recalled. “Since I had thrown the discus at Youree Drive [Junior High] and won consistently he said to go out and work with Jack Pyburn -- his 170-foot [state-record] discus ace -- in his sixth-period track class.”

So he became a discus thrower at Byrd and also a hurdler, although his junior high coach didn't think that would happen. But Turner had a vision.

“As I look back, he was a unique individual," Stu says. "He

had a knack for looking at a kid and dreaming of what [track or field] event that kid could do...and then he would sell it to him.”

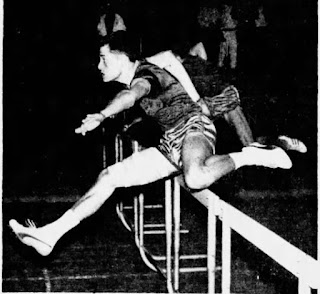

|

| Stewart Blue, Byrd High hurdler |

And Turner “flattered me by saying that I looked like a fine future hurdler....who could also throw the discus....and if I walked the way he said walk, talk the way he said talk, stay away from booze, cigarettes and girls, and remove the word ‘can't’ from my vocabulary, that he'd get me a scholarship in two years. At 6-4, 148 pounds, and nerdy, I bought into it.

“Then the unthinkable happened. I would win both hurdles races and the discus, a triple that was unheard of in track and field. As promised, two years later the [college] coaches started coming.”

That included majors (such as LSU, Tennessee, Baylor, Houston, Tulane), most of the state schools [then-Division II] and even the U.S. Military Academy was a possibility.

He made a last-minute decision to attend USL, not the usual call for a North Louisiana athlete or Byrd graduates, not what his family or friends recommended or wanted.

But he liked Lafayette from competing in the Southwestern Relays and he eventually found the area to his liking ... for good.

At USL, after a rough start and thoughts of transferring, he surprisingly began running the 440-yard dash and sprint relays, events he had not run at Byrd.

“Scared to death,” he recalled. “I began working under a grad assistant whose philosophy was that everyone is a quarter miler until they prove they can run something else.”

Another surprise: He adjusted quickly, setting a USL school record on his first try … at home in the Shreveport Relays college division on the Byrd track and beating ex-Byrd teammates Greg Falk and Jimmy Hughes, both All-Staters at Byrd who finished first and fourth in the state meet and were now at Northeast Louisiana.

It was especially a surprise for Coach Turner and Hughes, who “laughed at me” when he said he would run the 440 (because the hurdles field was filled). They weren’t laughing after the race.

That spring, he won the Gulf States Conference 440-yard title, again beating Hughes and Falk. (He won the event again as a senior in 1969.)

He settled in at USL after a rough start and thoughts of transferring, picked up a nickname “Bluebird,” and became the school's best quartermiler to that point.

And he built a good relationship with Bob Cole, the USL coach who put together a squad that won conference titles in Blue’s first three years there.

“After I graduated I traveled with Cole to all of the meets and helped him at home [meets],” Stu said of his start in officiating. “We fished constantly at his Toledo Bend camp after he retired in 1984 and when he was in town, I wined and dined him … still.

“He turned out to be my best man when I married and I took care of him while he fought cancer and until he died in 2007. I was honored when his children asked me to deliver his eulogy. Coaches called him my ‘daddy.’

“He had the personality of a brick wall. But he knew how to communicate and motivate and he knew how to love people, if not show it. John McDonnell (who came from Ireland to run distance races at USL in the mid-1960s), as the most prolific track coach in the NCAA of any sport, gave Cole credit for all of his successes and for teaching him how to motivate athletes.”

After graduation, Stu's goal was to be with the FBI, but it did not develop. What did after a few weeks of waiting was a position with a drug company in New Orleans. He went into sales and left in 1993 as Pfizer’s Houston-New Orleans district manager, starting his own consulting company with two former teammates.

Meanwhile, his track and field world expanded. He began helping USL conduct its home meets, expanded his area high school connections and when Pat Henry became the LSU coach in 1988, he found a champion.

Henry's LSU teams won 27 national championships until Texas A&M hired him away after the 2004 season, and he's added nine with the Aggies. And Stewart Blue is a believer.

“He has built the overall finest facilities in the world in College Station,” Stewart opines, “$100 million worth. Oregon will open its world’s finest outdoor facility next spring and I am anxious to be there working the [Olympic] Trials.”

He works meets at ULL, LSU and Arkansas, but with any conflict, his first allegiance is to A&M, no matter that it’s a five-hour trip.

“They do everything right,” he says, “and gave Pat a venue that has made track and field better.”

Stewart can (and does) name-drop many of the greats — athletes and coaches — he’s met, a who’s who of American track and field. Good story about one of them: Carl Lewis.

Lewis was helping coach at his alma mater, University of Houston, and as a meet referee, Stu had to ask him to leave the competition area during the long jump. Gist of story: He had to tell the gold-medal, prima donna (“Do you know who I am?”) to return to the coaching area in the stands.

Lewis finally did. As he walked away, Stu thought to himself, “Did I just say that to Carl Lewis?”

---

His Shreveport roots -- and plaudits -- return to two names.

|

| Jerry Byrd Jr., Byrd assistant principal, and Stewart Blue show off the 2017 Class 5A girls state championship trophy, the first in track and field for Byrd since Blue's senior year (1965). |

The second was Scotty Robertson. The bearer of bad news one day in the fall of 1962 gave him a moment to remember in 1974.

On one of Stewart’s working trips to Ruston, in Robertson's last year as basketball coach at Louisiana Tech, they had lunch and when he had to leave to get back home to help officiate a track meet, Scotty offered advice.

"He told me to get back to Lafayette and leave the sport better than I found (as an official)," Stu recalled. "He reminded me that I had competed at meets that didn't have many officials and that everything in my life -- jobs, people, relationships -- would be connected to and made possible by the free education I received because of track ... and I should give back to what has turned out to be a great life, as he predicted.

"And he was right.

“It's 50 years later, and I'm still trying,” he added. “I've been all over the country with the sport and have developed some great friendships with talented people. And it's been a labor of love for those friends and the sport.”

But the finish line is ahead. "The years to do that stuff are getting shorter," he says. "I'll go as long as my wife lets me, which might be 1-2-3 more years at most.

“I've been extremely blessed and remember my roots, and those who "brung" me.”

So he thanks the sport, and he's done his best to make it better.