A trip back in time, and another visit with Dad.

The name of the camp is Les Mazures. Remember that. It is the key to this story.

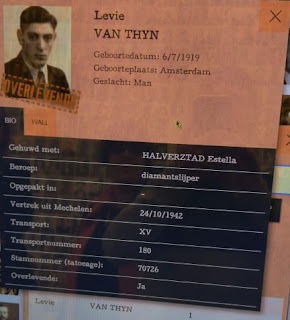

Look at these two photos. That's Dad -- Louis Van Thyn -- at ages 16 (almost 17) and 26 1/2.

This is the first time you have seen them. Because when we received them last week, it was the first time we had seen them.

It is, as you might imagine, a great find for us, a bit emotional.

With the photos came two dossiers, forms he had to fill to establish -- and re-establish -- residency in Belgium.

The name on those forms is Levi Van Thijn -- his original first name (Louis, or Louie, was a nickname he always was called); he had it legally changed once we were in the United States. The last name is the Dutch spelling (the y was written ij).

The first photo: May 1936 when he first arrived in Antwerp, Belgium, having left home in Amsterdam with his parents' permission, and his intention is learning the diamond cutting trade.

You can see how young -- innocent? -- he looks, wearing the glasses he wore as a kid (and never again until he was in his mid-50s) ... and, for some reason, glancing sideways.

The second photo: November 1945, a sharp-looking, much more seasoned and mature young man, a Holocaust survivor, a prisoner of the Germans/Nazis for nearly 2 1/2 years, much of that in concentration camps. Also a widower; his first wife, Estella, one of the six million Jews who died. He was unsure if she like him had been sent to Auschwitz.

He's back in Antwerp, at last, looking for a new life.

---

In his Holocaust interview, the one we used for much of the Survivors: 62511, 70726 book, Dad talked about where he went after the Nazis "arrested" him (and so many others) in the fall of 1942.

Page 45 ... First stop: a work camp in Northern France.

"We spent around three months there. ... It was by the town of Charleville, in the French Ardennes (the dense forest region) by the Belgium border," he told the interviewer.

Asked for the camp's name, he replied, "I don't think it had a name. ... I want to get there one day and see, but there is nothing there that you can see it was a camp." (He never made that visit.)

---

Of course the camp had a name. It is my fault that I did not research more, or ask more questions, to fill in the details.

But we found out the name last week: Les Mazures.

The names, Dad's photos and the dossiers were sent to us by Reinier Heinsman, who introduced himself to us last week as a volunteer for the Kazerne Dossin Museum in Belgium, a place I wrote about in 2014, located in Mechelen, a city halfway between Antwerp and Brussels.

It is on the site of the transition camp where Dad was sent after his stay at Les Mazures and from where he was sent by train to Auschwitz.

Reinier asked my Kazerne Dossin contact, Dorien Styven, for my e-mail, and so Reinier asked for information on my Dad's lifelong great friend, Joseph "Joopie" Scholte, and his family -- particularly photos of Joopie's older brother, Jonas, and Joopie's 2-year-old daughter Helene.

He also told me -- important connection -- that the Scholte boys and Dad had been at the "concentration camp of Les Mazures in northern France."

To be honest, that was news to me ... until I checked my blog and book (and found that Dad had not recalled the name).

So I confirmed with Reinier that his facts were correct.

Yael Reicher, who lives in Belgium and is a good friend of Reinier's, is president of the Memorial of the Concentration Camp of Les Mazures.

"She knows a lot about the camp and about all the prisoners," Reinier wrote. "She is very dedicated to preserving the memory of the camp and of all the people who were interned there, including her father." (And mine.)

Yael, too, confirmed this: "Both Louis and Jonas were indeed interned at the Judenlager [Jewish camp] of Les Mazures."

Much of the information that Yael sent and is in the dossiers is included in chapter 29 (pages 106-109) of the Survivors book.

https://nvanthyn.blogspot.com/2014/07/the-fate-of-family-in-belgium.html

That describes the Les Mazures work camp and its purpose, and we also received from Kazerne Dossin several years ago what information they had on Dad, Joopie and Jonas Scholte, and on Estella.

Can tell you that Dad, although he did not recall the camp name, is spot-on about the location and the work done there.

And typically for him, because he for the most part always kept his good nature and positive outlook despite all that happened to him, recalled that the Les Mazures experience wasn't that harsh, not like what was ahead.

---

Didn't think we had a photo of Jonas until my sister Elsa pointed out that he was in the wedding photo of Joopie and his first wife that we've had for years (and is in the book).

Indeed, Jonas is up front on the left, and Dad is in the back left. So we sent that photo to the people in Belgium, along with Dad's wedding photo with Estella.

We told Reinier and Yael -- who were not sure of the connection -- that the Scholtes' mother Leentje was a sister of Dad's mother, our grandmother Sara.

The dossier also shows a wedding date for Dad and Estella -- September 16, 1941. We knew the month and year, but not the date.

About the group known as the Association in Memory of the Judenlager of Les Mazures: A Belgian historian, Jean-Emile Andreux, did the research on the camp, published his work and created a memorial with the names of the 288 men deported from Antwerp to Les Mazures.

A monument was dedicated in 2005 on the site where the camp used to be. There is nothing left, except the foundations of the barracks and debris in the surrounding woods.

Every year there are two commemorations: (1) in July, the national French ceremony for victims of the Shoah (Holocaust); (2) on October 23, the date of the deportation to Auschwitz.

At the site, there are portraits of all but a dozen of the men deported, Dad included. And now Jonas' photo will be there, too.

The site itself is a soccer field today. I assure you: Dad would have loved that.

When and if I redo, or update, the Survivors book -- there are now nine Van Thyn great grandchildren -- it will be good to have information that corrects what was missing before.