Showing posts with label Shreveport-Bossier athletics. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Shreveport-Bossier athletics. Show all posts

Saturday, May 15, 2021

Monday, February 22, 2021

Monday, December 28, 2020

Tuesday, September 29, 2020

Stewart Blue, track and field: a love story

No one we know loves the sport of track and field more than Stewart Blue. He might have his equals, but no one loves it more.

And it's been that way for almost 60 years.

He was a standout high school track guy and even better in college ... and he has remained involved with the sport ever since, for decades now as a meet official, a timer, overseeing an event, as an umpire or as a referee.

So he knows the rules, he has to OK the disqualifications and he has to care ... and he does.

The tall man loves him some track and field, and appreciates its athletes.

If there is a meet at Texas A&M, he will be there. If there is a meet at LSU, count on Stu. The Louisiana high school state meets? He's missed only two since 1972, only because they conflicted with college conference championship meets to which he was committed.

|

| Stewart, with daughter Jamie and wife Karen. |

He loves his wife and his daughter, son-in-law and two grandkids, and he has a life. But track and field is, a part of his being.

A number of recent bouts with prostate and brain cancer have been hurdles to clear. But he's been hurdling since those early 1960s days at Byrd High School in Shreveport.

As a Byrd senior in 1965, he was part of the last state championship team for Coach Woodrow Turner, the last of nine top-class titles in a 12-year span. Blue finished second in both the high and low hurdles at the state meet.

He was a popular figure with competitors, open and friendly and garrulous, easy to spot (he's 6-foot-4) ... and talented.

He lives now, as he has for years, in Lafayette. But he also spends much time in Cut Off (deep on the bayou in southeast Louisiana; home of LSU head football coach Ed Orgeron). That's where daughter Jamie Blue Guidry lives with her family.

She is marketing director for the company that owned the plane that crashed in Lafayette last December on the day of the LSU-Oklahoma national semifinals football game, and Stu and his wife Karen have been in Cutoff to help with the two grandchildren.

And this year -- as with everyone else -- Stewart's track-field schedule was rudely interrupted. It ended with the SEC Indoor Championships before the pandemic hit.

But he’s looking ahead to 2021.

On the schedule — if conditions permit — are the SEC and NCAA indoor meets at Arkansas, the completion of his 45th year of meets at LSU, the Olympic Trials next summer as an umpire, and the referee job at the SEC Outdoor Championships at College Station in May.

For this article, however, we reflect and take a long look back.

---

Stewart credits Woodrow Turner and Scotty Robertson, two of his Byrd coaches — legends both — for giving him his greatest career boosts and motivation.

First, though, came a Robertson evaluation. After a week of basketball "games" and drills in a P.E. class as a sophomore in 1962, Stewart heard that basketball wasn't a fit.

Scotty's bad news: “He said that I couldn't walk and chew gum at the same time," Stu remembers. "The good news (for him) was that I would not a basketball player; that my name would be ’floor’ if I tried because I couldn’t jump off the floor.”

But Woodrow Turner, listening to that conversation, called Stu over to his desk.

“He started to flatter me, which was his norm,” he recalled. “Since I had thrown the discus at Youree Drive [Junior High] and won consistently he said to go out and work with Jack Pyburn -- his 170-foot [state-record] discus ace -- in his sixth-period track class.”

So he became a discus thrower at Byrd and also a hurdler, although his junior high coach didn't think that would happen. But Turner had a vision.

“As I look back, he was a unique individual," Stu says. "He

had a knack for looking at a kid and dreaming of what [track or field] event that kid could do...and then he would sell it to him.”

|

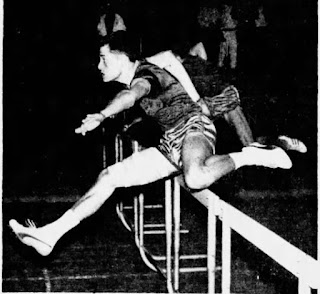

| Stewart Blue, Byrd High hurdler |

And Turner “flattered me by saying that I looked like a fine future hurdler....who could also throw the discus....and if I walked the way he said walk, talk the way he said talk, stay away from booze, cigarettes and girls, and remove the word ‘can't’ from my vocabulary, that he'd get me a scholarship in two years. At 6-4, 148 pounds, and nerdy, I bought into it.

“Then the unthinkable happened. I would win both hurdles races and the discus, a triple that was unheard of in track and field. As promised, two years later the [college] coaches started coming.”

That included majors (such as LSU, Tennessee, Baylor, Houston, Tulane), most of the state schools [then-Division II] and even the U.S. Military Academy was a possibility.

He made a last-minute decision to attend USL, not the usual call for a North Louisiana athlete or Byrd graduates, not what his family or friends recommended or wanted.

But he liked Lafayette from competing in the Southwestern Relays and he eventually found the area to his liking ... for good.

At USL, after a rough start and thoughts of transferring, he surprisingly began running the 440-yard dash and sprint relays, events he had not run at Byrd.

“Scared to death,” he recalled. “I began working under a grad assistant whose philosophy was that everyone is a quarter miler until they prove they can run something else.”

Another surprise: He adjusted quickly, setting a USL school record on his first try … at home in the Shreveport Relays college division on the Byrd track and beating ex-Byrd teammates Greg Falk and Jimmy Hughes, both All-Staters at Byrd who finished first and fourth in the state meet and were now at Northeast Louisiana.

It was especially a surprise for Coach Turner and Hughes, who “laughed at me” when he said he would run the 440 (because the hurdles field was filled). They weren’t laughing after the race.

That spring, he won the Gulf States Conference 440-yard title, again beating Hughes and Falk. (He won the event again as a senior in 1969.)

He settled in at USL after a rough start and thoughts of transferring, picked up a nickname “Bluebird,” and became the school's best quartermiler to that point.

And he built a good relationship with Bob Cole, the USL coach who put together a squad that won conference titles in Blue’s first three years there.

“After I graduated I traveled with Cole to all of the meets and helped him at home [meets],” Stu said of his start in officiating. “We fished constantly at his Toledo Bend camp after he retired in 1984 and when he was in town, I wined and dined him … still.

“He turned out to be my best man when I married and I took care of him while he fought cancer and until he died in 2007. I was honored when his children asked me to deliver his eulogy. Coaches called him my ‘daddy.’

“He had the personality of a brick wall. But he knew how to communicate and motivate and he knew how to love people, if not show it. John McDonnell (who came from Ireland to run distance races at USL in the mid-1960s), as the most prolific track coach in the NCAA of any sport, gave Cole credit for all of his successes and for teaching him how to motivate athletes.”

After graduation, Stu's goal was to be with the FBI, but it did not develop. What did after a few weeks of waiting was a position with a drug company in New Orleans. He went into sales and left in 1993 as Pfizer’s Houston-New Orleans district manager, starting his own consulting company with two former teammates.

Meanwhile, his track and field world expanded. He began helping USL conduct its home meets, expanded his area high school connections and when Pat Henry became the LSU coach in 1988, he found a champion.

Henry's LSU teams won 27 national championships until Texas A&M hired him away after the 2004 season, and he's added nine with the Aggies. And Stewart Blue is a believer.

“He has built the overall finest facilities in the world in College Station,” Stewart opines, “$100 million worth. Oregon will open its world’s finest outdoor facility next spring and I am anxious to be there working the [Olympic] Trials.”

He works meets at ULL, LSU and Arkansas, but with any conflict, his first allegiance is to A&M, no matter that it’s a five-hour trip.

“They do everything right,” he says, “and gave Pat a venue that has made track and field better.”

Stewart can (and does) name-drop many of the greats — athletes and coaches — he’s met, a who’s who of American track and field. Good story about one of them: Carl Lewis.

Lewis was helping coach at his alma mater, University of Houston, and as a meet referee, Stu had to ask him to leave the competition area during the long jump. Gist of story: He had to tell the gold-medal, prima donna (“Do you know who I am?”) to return to the coaching area in the stands.

Lewis finally did. As he walked away, Stu thought to himself, “Did I just say that to Carl Lewis?”

---

His Shreveport roots -- and plaudits -- return to two names.

|

| Jerry Byrd Jr., Byrd assistant principal, and Stewart Blue show off the 2017 Class 5A girls state championship trophy, the first in track and field for Byrd since Blue's senior year (1965). |

The second was Scotty Robertson. The bearer of bad news one day in the fall of 1962 gave him a moment to remember in 1974.

On one of Stewart’s working trips to Ruston, in Robertson's last year as basketball coach at Louisiana Tech, they had lunch and when he had to leave to get back home to help officiate a track meet, Scotty offered advice.

"He told me to get back to Lafayette and leave the sport better than I found (as an official)," Stu recalled. "He reminded me that I had competed at meets that didn't have many officials and that everything in my life -- jobs, people, relationships -- would be connected to and made possible by the free education I received because of track ... and I should give back to what has turned out to be a great life, as he predicted.

"And he was right.

“It's 50 years later, and I'm still trying,” he added. “I've been all over the country with the sport and have developed some great friendships with talented people. And it's been a labor of love for those friends and the sport.”

But the finish line is ahead. "The years to do that stuff are getting shorter," he says. "I'll go as long as my wife lets me, which might be 1-2-3 more years at most.

“I've been extremely blessed and remember my roots, and those who "brung" me.”

So he thanks the sport, and he's done his best to make it better.

Sunday, January 13, 2019

Book? What book? Try a series of blogs

That's the old ballgame Shreveport.

OK, the goal was to publish a book on the history of professional baseball in Shreveport and North Louisiana.

So much for this goal.

On October 3 last year, I posted a blog about the research process, the idea for the book, and where it stood.

It is no longer standing. It is not going to happen, not from me, anyway. Maybe someone else. Good luck.

https://nvanthyn.blogspot.com/2018/10/researching-baseball-is-history.html

But two years of research and of collecting photos are not going empty. So -- if you care to read and look at what I have -- stay tuned. It is going to turn into a series of blog pieces.

This will take a while. There are 28 chapters ready, plus an introduction, and acknowledgements. Some of the material has been on my blog previously, so if you have seen it before, forgive me.

If we post one a week, say on Mondays, that should carry us into August -- and then it will be time again for football.

True, many of the people on our e-mail list and Facebook "friends" won't care about baseball, period, and even moreso about baseball in Shreveport and the area.

For the ones who do care, hope you enjoy it. It is a walk -- a free pass -- back into a time when Shreveport and North Louisiana mattered in baseball.

Still does in a sense through the great names who came through town and in the players from our area who made it in the game -- many to the major leagues -- and those who are still active.

So, why no book? First, too expensive. Wanted to do color, and there is a big price for that. Might have been too much even in black-and-white. Second -- and perhaps the main reason -- the use of photos.

Many photos I collected -- off the Internet, from newspaper clippings, and many from the Texas League office in downtown Fort Worth -- are copyrighted.

For instance, there are a great number of photos from The Shreveport Times, while ended up with the Shreveport Captains. When the longtime ownership group sold the team, those photos -- and even championship trophies -- were donated to the TL office.

The friend -- a newspaper editor -- who formatted the book on my parents and our family looked at the baseball material and we talked about the possible copyright problems.

It did not take me long to make a decision: no book.

Hoping that using photos on my blog will not cause problems. In six years of blogging, I have never had an issue in that regard. I will credit the sources when I think I should.

Knew that what I had in mind for a book likely was overreach, and too expensive -- afraid of what the printing cost might have been, even in a black-and-white format -- and the fallback position always had been to present the material on my blog.

That's what I am going to do. The material is ready and if you want to say this is the easy way to do it, I am fine with that.

Presented proposals to four publishing companies -- three based in Louisiana. No takers.

A company in South Carolina that has published a series of historical books, including on baseball in cities comparable to Shreveport, did show interest. But their baseball books, while very interesting, were more photo-based than I preferred. And, again, I do not have photo rights than I can verify (or possible pay for, if needed).

Plus, and pardon the self-interest view, I like the written material I have gathered. Hopefully, some others will like it, too.

Professional baseball in Shreveport -- since 2011 -- is dormant. Thus, the prospective title: That's the old ballgame Shreveport.

So there is not much updating to be done, except for the active major leaguers from our area (Seth Lugo, from Parkway High in Bossier City and Centenary College, is one).

And who knows if pro baseball will return there? It does not seem likely right now. We have to live with the history of the Gassers, Sports, Captains and -- yes -- Swamp Dragons.

It is, to me, an interesting history. And if one wants to check my blog pieces from now through about 30 weeks, it will be there.

OK, the goal was to publish a book on the history of professional baseball in Shreveport and North Louisiana.

So much for this goal.

On October 3 last year, I posted a blog about the research process, the idea for the book, and where it stood.

It is no longer standing. It is not going to happen, not from me, anyway. Maybe someone else. Good luck.

https://nvanthyn.blogspot.com/2018/10/researching-baseball-is-history.html

|

| This is what the inside title page would have been. |

This will take a while. There are 28 chapters ready, plus an introduction, and acknowledgements. Some of the material has been on my blog previously, so if you have seen it before, forgive me.

If we post one a week, say on Mondays, that should carry us into August -- and then it will be time again for football.

True, many of the people on our e-mail list and Facebook "friends" won't care about baseball, period, and even moreso about baseball in Shreveport and the area.

For the ones who do care, hope you enjoy it. It is a walk -- a free pass -- back into a time when Shreveport and North Louisiana mattered in baseball.

Still does in a sense through the great names who came through town and in the players from our area who made it in the game -- many to the major leagues -- and those who are still active.

So, why no book? First, too expensive. Wanted to do color, and there is a big price for that. Might have been too much even in black-and-white. Second -- and perhaps the main reason -- the use of photos.

Many photos I collected -- off the Internet, from newspaper clippings, and many from the Texas League office in downtown Fort Worth -- are copyrighted.

For instance, there are a great number of photos from The Shreveport Times, while ended up with the Shreveport Captains. When the longtime ownership group sold the team, those photos -- and even championship trophies -- were donated to the TL office.

The friend -- a newspaper editor -- who formatted the book on my parents and our family looked at the baseball material and we talked about the possible copyright problems.

It did not take me long to make a decision: no book.

Hoping that using photos on my blog will not cause problems. In six years of blogging, I have never had an issue in that regard. I will credit the sources when I think I should.

Knew that what I had in mind for a book likely was overreach, and too expensive -- afraid of what the printing cost might have been, even in a black-and-white format -- and the fallback position always had been to present the material on my blog.

That's what I am going to do. The material is ready and if you want to say this is the easy way to do it, I am fine with that.

Presented proposals to four publishing companies -- three based in Louisiana. No takers.

A company in South Carolina that has published a series of historical books, including on baseball in cities comparable to Shreveport, did show interest. But their baseball books, while very interesting, were more photo-based than I preferred. And, again, I do not have photo rights than I can verify (or possible pay for, if needed).

Plus, and pardon the self-interest view, I like the written material I have gathered. Hopefully, some others will like it, too.

Professional baseball in Shreveport -- since 2011 -- is dormant. Thus, the prospective title: That's the old ballgame Shreveport.

So there is not much updating to be done, except for the active major leaguers from our area (Seth Lugo, from Parkway High in Bossier City and Centenary College, is one).

And who knows if pro baseball will return there? It does not seem likely right now. We have to live with the history of the Gassers, Sports, Captains and -- yes -- Swamp Dragons.

It is, to me, an interesting history. And if one wants to check my blog pieces from now through about 30 weeks, it will be there.

Tuesday, January 8, 2019

He ran into history, and lived a life

He was one of our "Cinderella" Knights, a significant one who made a run into history.

For me, James Rice was the older kid who lived in the next block on Amherst Street in Sunset Acres, a nice guy, always friendly. And he could run fast.

He was one of my heroes, like so many on those first two Woodlawn Knights football teams. But we especially loved our guys (and gals) from Sunset Acres.

So it was with some sorrow when the well-after-the-fact news came -- from a couple of sources -- that James Dewayne Rice died October 23, 2018, at a nursing home in Shreveport, age 74.

So it was with some sorrow when the well-after-the-fact news came -- from a couple of sources -- that James Dewayne Rice died October 23, 2018, at a nursing home in Shreveport, age 74.

Had not seen an obit in the paper. What we did see, confirmation of his passing, was a "findagrave" post.

James Rice -- football halfback and safety (even at 130 pounds), track sprinter, hard-working and dedicated in athletics and as a longtime hotel/motel employee and manager, responsible older brother, husband, father, grandfather ... friend.

Another loss from "The Team Named Desire." Don't like those. That team, as a whole, was among the biggest winners we have ever known.

And it is with some surprise to learn that James' life wasn't a Cinderella story, that what followed after the "Camelot" chapters was an often mixed journey.

As with many of us, most of us, there was success and struggle. Happiness, and sad times.

Turmoil at home in his early life. Love, a lengthy marriage (to Phoebe), and divorce. Two children (a daughter and a son who is a Notre Dame graduate), and then estrangement. Good jobs, steady ones, and then failure. Several moves -- to points east. One grandson, and although there was distance, monthly financial aid almost to the end.

In the last few years, there was dementia/Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, diabetes, alcohol, a move back to Shreveport, a place to live and with two women (his younger sister and her best friend) looking after him, stays in hospitals and nursing homes ... and the final decline.

But our memories, and those of good friends, are sweet.

"He was very reserved, quiet, and very smart," said Jerry Downing, one of his closest friends in the Sunset Acres years, a teammate on many athletics teams.

"He was, to me, the golden boy," said Andra Wilson, who in high school dated James steadily for a year and then on-and-off after that. "He was supposed to have had a successful life, not only financially.

"He was disciplined, made excellent grades ... worked a parttime [filling station] job."

Johnny Maxwell, a longtime hotel/restaurant operator in Ruston (and other places), was one of James' benefactors, and his longtime boss.

"I thought a lot of James," said Maxwell, 81, still a Ruston resident. "He was a good guy, a kind guy; he would do anything for anybody if he could.

"I loved him like a brother. I tried to help him along."

Connie Reed Roge' literally loved him like a brother. She was his youngest sister (nine years younger), a premature baby (1 1/4 pounds at birth), and so there was a bond.

In Sunset Acres, their mother worked, the stepfather was in-and-out and difficult, and James often was in charge of the four younger children (whose last name was Reed).

"He took care of all of us, babysat us all the time," Connie recalled.

She mentioned that the teenage James, while Mom worked, liked talking on the phone to his girlfriend, perhaps a little longer than what was acceptable.

"Don't tell Mama, don't tell Mama," he instructed his siblings. But to be sure that would not happen, he promised to make oatmeal cookies for them. A bribe.

He had the recipe, perhaps from home ec classes, and kept the recipe for years. "He could cook," Connie recalled.

When their mother died in 1969, Connie was 16, James was working in Ruston, and he helped her move in with an aunt and checked on her often.

"We were always close," Connie said, "but after a while, he moved away. So we kept in touch by phone, but didn't see each other much because of the distance."

Her payback to him would come decades later.

---

When we knew him, he had gone through Sunset Acres Elementary, then Midway Junior High, a sophomore year at Fair Park High and on to Woodlawn when it opened in the fall of 1960.

Which brings us to football.

Which brings us to football.

On October 19, 1960, junior halfback James Rice -- small, thin and fast -- made history: He ran 57 yards for the first varsity touchdown in Woodlawn history.

After the Knights had been shut out in their first four games, James hit the end zone -- and he did it against the school that would become our arch-rival, Byrd, and against a Byrd team that was ranked No. 1 in the state and would go unbeaten that regular season. I won't bother to give you the score of that game, but Woodlawn had 6 points.

(Bobby Glasgow, a sophomore that year, will tell you that he scored the first Woodlawn touchdown -- and he did ... but for the B-team a week earlier. It was a varsity game, but only for Haughton.)

(Bobby Glasgow, a sophomore that year, will tell you that he scored the first Woodlawn touchdown -- and he did ... but for the B-team a week earlier. It was a varsity game, but only for Haughton.)

James had been a B-team back for Fair Park in 1959, then came to Woodlawn with a rag-tag bunch of players -- a few seniors, but a lot of juniors (transfers from Byrd, Fair Park and Greenwood) and sophomores fresh out of junior high.

Wrote about that team in the first year of my blog, almost 6 1/2 years ago: http://nvanthyn.blogspot.com/2012/08/the-team-named-desire.html

James started two seasons for Woodlawn -- the awful first season (0-9 record), the second (his senior year) a glorious, astounding district championship -- a 9-2 regular-season record in which they kept winning games with fourth-quarter heroics. The Knights' first playoff game followed.

That very small physical team -- Rice at 140 by his senior year had lots of company in the "lightweight" category; an offensive guard weighed 145, a tackle 165. Only one starter, a tackle, had any real size (for then) -- 195 pounds.

This was a quick, supremely conditioned, mentally tough -- and talented -- team. The Team Named Desire. The "Cinderella" Knights. A Cinderella story.

This was a quick, supremely conditioned, mentally tough -- and talented -- team. The Team Named Desire. The "Cinderella" Knights. A Cinderella story.

There were a half dozen future college players -- some all-conference ones -- on this team. Not James (too small), but he was one of the top stars. Check the clippings. And he scored the final touchdown of the season -- in the state playoff game.

Downing was the 160-pound center on those teams (and the starting catcher in baseball), and always James' friend. He lived two blocks away on Sunnybrook, across from the well-known scout hut on the Sunset Acres Elementary grounds.

"He was in my first wedding," Downing said, "and we each delivered newspapers, we had newspaper routes. We would go near the A&P store in the Sunset shopping center early in the mornings to pick up our papers, and vendors would leave us honeybuns and chocolate milk. The store manager was OK with that, as long as we cleaned up the area. We were barely teenagers.

"We played on a lot of teams together. Everyone knew he was a fast runner."

And in high school, they often joined with [end] Ted Bounds for, well, some joy rides in Ted's Rambler.

Downing, too, was at Louisiana Tech at the same time as Rice, and "we had a great time playing flag football.

"What a great loss, and I hope to see him again on the other side. ..."

Ronnie Mercer, at 135 pounds, was James' partner at safety in football and also a good friend through the La. Tech years.

"When we were in Ruston, we lived in a four-plex and James and Phoebe were our next-door neighbors," Mercer recalled. "I don't think I ever saw him angry, which was a complement to the angry person I was.

"He deserves to be written about. He was a man of tremendous heart."

Mercer remembered one football incident at State Fair Stadium (now Independence Stadium)

"Don't remember who we were playing, but we were on defense and James made a tackle and it knocked him goofy," Mercer said. "He actually went and lined up in the other team's huddle. I don't think anyone noticed until they broke the huddle to run the play. Then one of the referees noticed. But I guess he was going to run the offensive play for the other team."

In the long run, Woodlawn football was a memorable experience for James Rice, for all of us 1960s kids. The long run of his life -- a little more than 57 years after that 57-yard run -- was a bigger test.

In the long run, Woodlawn football was a memorable experience for James Rice, for all of us 1960s kids. The long run of his life -- a little more than 57 years after that 57-yard run -- was a bigger test.

---

College was in his plans, but money was short. His stepfather promised to pay to start his education ... if James would work at his filling station that summer. But the deal fell through, and helped was needed.

It came from then-Woodlawn counselor Mary Higginbotham, who had Louisiana Tech and Ruston connections (and a year went to work at Tech).

Mrs. Higginbotham called her friend Johnny Maxwell, recent new owner/operator of the Holiday Inn near the Tech campus, and asked if he could find James a job and a place to live.

"I can do that," Maxwell told her. Some of us remember James working at the Holiday Inn during his college years and then becoming a fulltime employee, first as restaurant manager.

He met Phoebe, married and soon they started a family.

After some years, it was time to move on. After a job for a food company in Jackson, Miss., James knew Maxwell had bought the Holiday Inn in Oxford, Miss., and asked if he had a job for him there. He did: manager.

He was a neat dresser and he learned to do the maintenance job required to keep a hotel/motel in top shape.

From there, it was on to another hotel managing job in Augusta, Georgia -- home of the Masters golf tournament. One year Maxwell took his son and grandson to the tournament, and James arranged tickets and a place for them to stay.

After the divorce, as Maxwell recalled, "he went off the radar for a number of years" and moved to Meridian, Mississippi.

Some years later, Connie got word that there were gaps in James' managing his life.

She and husband Harold went to Meridian, packed up his belongings and brought him back to Shreveport. Contact with his ex-wife and children ended, but his grandson remained in his thoughts.

---

He loved going to church, loved the dog "Lil' Man" he was given, took him for walks every day at the Southern Hills recreation park. He worked in gardens and tended to roses he planted.

Over the past couple of weeks, Connie and Shirley Weaver have put together memories of James for the memorial, which will happen two days before what would have been his 75th birthday.

Over the past couple of weeks, Connie and Shirley Weaver have put together memories of James for the memorial, which will happen two days before what would have been his 75th birthday.

"I am glad that he did not suffer long," said Connie of the last part of James' life.

"He was such a kind, loving person," said Shirley, "... He was loved by many."

And in the final year, some old friends -- Maxwell, some of James' working employees, and a few Woodlawn buddies -- came to visit him.

Long-ago girlfriend Andra Wilson, reflecting on James' final years, said the stories she heard "have kept me aware; I have had nightmares ... James was kind of a naive guy, but he was sweet."

As Connie worked to arrange a memorial, she said, "Talking to all of ya'll [James' old friends] has helped me with closure about James."

Because he loved the song The Rose, the Conway Twitty version, that will be part of his memorial.

He will be -- he is -- fondly remembered by many of us. He not only ran into history, he ran into a place in our hearts and memories.

---

A memorial for James Rice (WHS Class of '62) is scheduled Saturday, January 19, 1 p.m., 11055 General Patton Avenue, Shreveport (Connie Roge's house). Please contact Connie at 318-453-4902 or 318-687-6369 if you plan to attend, and share your thoughts at the memorial.

For me, James Rice was the older kid who lived in the next block on Amherst Street in Sunset Acres, a nice guy, always friendly. And he could run fast.

He was one of my heroes, like so many on those first two Woodlawn Knights football teams. But we especially loved our guys (and gals) from Sunset Acres.

So it was with some sorrow when the well-after-the-fact news came -- from a couple of sources -- that James Dewayne Rice died October 23, 2018, at a nursing home in Shreveport, age 74.

So it was with some sorrow when the well-after-the-fact news came -- from a couple of sources -- that James Dewayne Rice died October 23, 2018, at a nursing home in Shreveport, age 74.Had not seen an obit in the paper. What we did see, confirmation of his passing, was a "findagrave" post.

James Rice -- football halfback and safety (even at 130 pounds), track sprinter, hard-working and dedicated in athletics and as a longtime hotel/motel employee and manager, responsible older brother, husband, father, grandfather ... friend.

Another loss from "The Team Named Desire." Don't like those. That team, as a whole, was among the biggest winners we have ever known.

And it is with some surprise to learn that James' life wasn't a Cinderella story, that what followed after the "Camelot" chapters was an often mixed journey.

As with many of us, most of us, there was success and struggle. Happiness, and sad times.

Turmoil at home in his early life. Love, a lengthy marriage (to Phoebe), and divorce. Two children (a daughter and a son who is a Notre Dame graduate), and then estrangement. Good jobs, steady ones, and then failure. Several moves -- to points east. One grandson, and although there was distance, monthly financial aid almost to the end.

In the last few years, there was dementia/Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, diabetes, alcohol, a move back to Shreveport, a place to live and with two women (his younger sister and her best friend) looking after him, stays in hospitals and nursing homes ... and the final decline.

But our memories, and those of good friends, are sweet.

"He was very reserved, quiet, and very smart," said Jerry Downing, one of his closest friends in the Sunset Acres years, a teammate on many athletics teams.

"He was, to me, the golden boy," said Andra Wilson, who in high school dated James steadily for a year and then on-and-off after that. "He was supposed to have had a successful life, not only financially.

"He was disciplined, made excellent grades ... worked a parttime [filling station] job."

Johnny Maxwell, a longtime hotel/restaurant operator in Ruston (and other places), was one of James' benefactors, and his longtime boss.

"I thought a lot of James," said Maxwell, 81, still a Ruston resident. "He was a good guy, a kind guy; he would do anything for anybody if he could.

"I loved him like a brother. I tried to help him along."

Connie Reed Roge' literally loved him like a brother. She was his youngest sister (nine years younger), a premature baby (1 1/4 pounds at birth), and so there was a bond.

In Sunset Acres, their mother worked, the stepfather was in-and-out and difficult, and James often was in charge of the four younger children (whose last name was Reed).

"He took care of all of us, babysat us all the time," Connie recalled.

She mentioned that the teenage James, while Mom worked, liked talking on the phone to his girlfriend, perhaps a little longer than what was acceptable.

"Don't tell Mama, don't tell Mama," he instructed his siblings. But to be sure that would not happen, he promised to make oatmeal cookies for them. A bribe.

He had the recipe, perhaps from home ec classes, and kept the recipe for years. "He could cook," Connie recalled.

When their mother died in 1969, Connie was 16, James was working in Ruston, and he helped her move in with an aunt and checked on her often.

"We were always close," Connie said, "but after a while, he moved away. So we kept in touch by phone, but didn't see each other much because of the distance."

Her payback to him would come decades later.

---

When we knew him, he had gone through Sunset Acres Elementary, then Midway Junior High, a sophomore year at Fair Park High and on to Woodlawn when it opened in the fall of 1960.

Which brings us to football.

Which brings us to football. On October 19, 1960, junior halfback James Rice -- small, thin and fast -- made history: He ran 57 yards for the first varsity touchdown in Woodlawn history.

After the Knights had been shut out in their first four games, James hit the end zone -- and he did it against the school that would become our arch-rival, Byrd, and against a Byrd team that was ranked No. 1 in the state and would go unbeaten that regular season. I won't bother to give you the score of that game, but Woodlawn had 6 points.

(Bobby Glasgow, a sophomore that year, will tell you that he scored the first Woodlawn touchdown -- and he did ... but for the B-team a week earlier. It was a varsity game, but only for Haughton.)

(Bobby Glasgow, a sophomore that year, will tell you that he scored the first Woodlawn touchdown -- and he did ... but for the B-team a week earlier. It was a varsity game, but only for Haughton.)James had been a B-team back for Fair Park in 1959, then came to Woodlawn with a rag-tag bunch of players -- a few seniors, but a lot of juniors (transfers from Byrd, Fair Park and Greenwood) and sophomores fresh out of junior high.

Wrote about that team in the first year of my blog, almost 6 1/2 years ago: http://nvanthyn.blogspot.com/2012/08/the-team-named-desire.html

James started two seasons for Woodlawn -- the awful first season (0-9 record), the second (his senior year) a glorious, astounding district championship -- a 9-2 regular-season record in which they kept winning games with fourth-quarter heroics. The Knights' first playoff game followed.

That very small physical team -- Rice at 140 by his senior year had lots of company in the "lightweight" category; an offensive guard weighed 145, a tackle 165. Only one starter, a tackle, had any real size (for then) -- 195 pounds.

This was a quick, supremely conditioned, mentally tough -- and talented -- team. The Team Named Desire. The "Cinderella" Knights. A Cinderella story.

This was a quick, supremely conditioned, mentally tough -- and talented -- team. The Team Named Desire. The "Cinderella" Knights. A Cinderella story.There were a half dozen future college players -- some all-conference ones -- on this team. Not James (too small), but he was one of the top stars. Check the clippings. And he scored the final touchdown of the season -- in the state playoff game.

Downing was the 160-pound center on those teams (and the starting catcher in baseball), and always James' friend. He lived two blocks away on Sunnybrook, across from the well-known scout hut on the Sunset Acres Elementary grounds.

"He was in my first wedding," Downing said, "and we each delivered newspapers, we had newspaper routes. We would go near the A&P store in the Sunset shopping center early in the mornings to pick up our papers, and vendors would leave us honeybuns and chocolate milk. The store manager was OK with that, as long as we cleaned up the area. We were barely teenagers.

"We played on a lot of teams together. Everyone knew he was a fast runner."

And in high school, they often joined with [end] Ted Bounds for, well, some joy rides in Ted's Rambler.

Downing, too, was at Louisiana Tech at the same time as Rice, and "we had a great time playing flag football.

"What a great loss, and I hope to see him again on the other side. ..."

Ronnie Mercer, at 135 pounds, was James' partner at safety in football and also a good friend through the La. Tech years.

"When we were in Ruston, we lived in a four-plex and James and Phoebe were our next-door neighbors," Mercer recalled. "I don't think I ever saw him angry, which was a complement to the angry person I was.

"He deserves to be written about. He was a man of tremendous heart."

Mercer remembered one football incident at State Fair Stadium (now Independence Stadium)

"Don't remember who we were playing, but we were on defense and James made a tackle and it knocked him goofy," Mercer said. "He actually went and lined up in the other team's huddle. I don't think anyone noticed until they broke the huddle to run the play. Then one of the referees noticed. But I guess he was going to run the offensive play for the other team."

In the long run, Woodlawn football was a memorable experience for James Rice, for all of us 1960s kids. The long run of his life -- a little more than 57 years after that 57-yard run -- was a bigger test.

In the long run, Woodlawn football was a memorable experience for James Rice, for all of us 1960s kids. The long run of his life -- a little more than 57 years after that 57-yard run -- was a bigger test. ---

College was in his plans, but money was short. His stepfather promised to pay to start his education ... if James would work at his filling station that summer. But the deal fell through, and helped was needed.

It came from then-Woodlawn counselor Mary Higginbotham, who had Louisiana Tech and Ruston connections (and a year went to work at Tech).

Mrs. Higginbotham called her friend Johnny Maxwell, recent new owner/operator of the Holiday Inn near the Tech campus, and asked if he could find James a job and a place to live.

"I can do that," Maxwell told her. Some of us remember James working at the Holiday Inn during his college years and then becoming a fulltime employee, first as restaurant manager.

He met Phoebe, married and soon they started a family.

After some years, it was time to move on. After a job for a food company in Jackson, Miss., James knew Maxwell had bought the Holiday Inn in Oxford, Miss., and asked if he had a job for him there. He did: manager.

He was a neat dresser and he learned to do the maintenance job required to keep a hotel/motel in top shape.

From there, it was on to another hotel managing job in Augusta, Georgia -- home of the Masters golf tournament. One year Maxwell took his son and grandson to the tournament, and James arranged tickets and a place for them to stay.

After the divorce, as Maxwell recalled, "he went off the radar for a number of years" and moved to Meridian, Mississippi.

Some years later, Connie got word that there were gaps in James' managing his life.

She and husband Harold went to Meridian, packed up his belongings and brought him back to Shreveport. Contact with his ex-wife and children ended, but his grandson remained in his thoughts.

---

He loved going to church, loved the dog "Lil' Man" he was given, took him for walks every day at the Southern Hills recreation park. He worked in gardens and tended to roses he planted.

Over the past couple of weeks, Connie and Shirley Weaver have put together memories of James for the memorial, which will happen two days before what would have been his 75th birthday.

Over the past couple of weeks, Connie and Shirley Weaver have put together memories of James for the memorial, which will happen two days before what would have been his 75th birthday."I am glad that he did not suffer long," said Connie of the last part of James' life.

"He was such a kind, loving person," said Shirley, "... He was loved by many."

And in the final year, some old friends -- Maxwell, some of James' working employees, and a few Woodlawn buddies -- came to visit him.

Long-ago girlfriend Andra Wilson, reflecting on James' final years, said the stories she heard "have kept me aware; I have had nightmares ... James was kind of a naive guy, but he was sweet."

As Connie worked to arrange a memorial, she said, "Talking to all of ya'll [James' old friends] has helped me with closure about James."

Because he loved the song The Rose, the Conway Twitty version, that will be part of his memorial.

He will be -- he is -- fondly remembered by many of us. He not only ran into history, he ran into a place in our hearts and memories.

---

A memorial for James Rice (WHS Class of '62) is scheduled Saturday, January 19, 1 p.m., 11055 General Patton Avenue, Shreveport (Connie Roge's house). Please contact Connie at 318-453-4902 or 318-687-6369 if you plan to attend, and share your thoughts at the memorial.

Wednesday, February 21, 2018

Thanks, NCAA ... your timing is absurd

|

| Robert Parish at Centenary (The Shreveport Times photo) |

---

It is not often -- ever? -- that "Centenary basketball" and "Son of Sam" gets used in the same sentence. There you have it!

This is all due to the recent announcement that the NCAA will now officially recognize Robert Parish's statistics while he played for the Gents in the 1970s. As David Berkowitz -- 1970s serial killer in New York City known as "Son of Sam" -- said when they came to arrest him, "What took you so long?"

The beginning and the end to this story defy description as far as absurdity is concerned. To make a very long story short, back in 1972 when Parish was about to enter Centenary, the NCAA used a formula based on high school grades and standardized tests to predict a player's GPA, which needed to equate to at least a 1.600. But Parish didn't take the SAT, so Centenary converted his score from the ACT and used that for the NCAA formula. Centenary had done this for the previous two years and nary a peep. But when the No. 1 recruit in the nation showed up, the NCAA took notice and told Centenary that the move was "illegal." (Parish wasn't the only Gents player who this had been applied to.) So the NCAA dropped six years on probation on the Gents -- unless they yanked the scholarships of Parish and four others. Centenary told the NCAA to go jump in the lake.

(One questions remains more than 45 years later: Why didn't Parish and the others just take the SAT? It's not like they have to achieve a Harvard-like score.)

Eventually the NCAA did away with the formula (called the 1.6 rule), but still stuck the hammer to Centenary. There is the favorite (and often misquoted) line by famed coach Jerry Tarkanian, who often said (kind of): "Every time the NCAA gets mad at (UCLA/Kentucky/other big guys), they add another two years' probation to (Centenary/Cleveland State/other little guys). Tarkanian filled in whatever blanks he needed to fit the audience, but the message was clear -- Centenary was getting hosed.

Parish and others could have gone anywhere else and been instantly eligible, but they stayed on Kings Highway and had a memorable four-year run.

When it was over, he had 2,334 points and 1,820 rebounds, but you'd never know it because the NCAA did not recognize his stats in its record book. Only two players in the history of college basketball have more points AND rebounds than Parish's totals.

So what happened? Did someone wake up at the NCAA one day last week and say, "OK, it's been 40 years. Enough's enough?" Were there protest marches outside the NCAA office and they were worried about the PR hit they were taking?

Actually, to Centenary's credit, the school made an appeal last year to the NCAA seeking "reinstatement." After they woke up the guy in charge of such things, the appeal was granted. And then the NCAA turned around and slapped Louisville around by denying its appeal of the vacated 2013 championship.

Somewhere out there, Jerry Tarkanian is smiling.

---

My take (as a sportswriter who wrote about Parish's high school and college careers in Shreveport):

Surprised by this, but I am not thrilled about it. It's OK.

It was so long ago, and the NCAA's "banishment" of the Parish statistics did not hurt his fabulous Basketball Hall of Fame career at all.

Don't see that it makes a lot of difference now, except for the principle that the NCAA -- after 42 to 46 years -- is admitting how petty it was in 1973-76.

Centenary benefited greatly from Parish being in school there, Robert and his family benefited greatly, and so did the basketball fans of Shreveport-Bossier and North Louisiana.

Can't tell you that Centenary did not break rules in admitting Robert to school. LSU (Dale Brown) and Indiana (Bob Knight) gladly would have taken him in their program, but were clear to Parish's high school coach (Ken Ivy) that he would not qualify academically.

Still, what the NCAA did to Centenary was best captured by then-Gents athletic director/head basketball coach Larry Little's remark that Centenary was given a death-penalty sentence for a speeding ticket.

Parish, in those years, got enough publicity to be known in many parts of the nation; I know this because I was the Centenary sports information director his senior season and set up several interviews with writers from other areas.

Plus, we sent out a flier touting Robert's accomplishments to most major newspapers and college/pro basketball sources in the country, and each week the NCAA statistics came out, we made sure to note where Robert would have ranked in points, rebounds, shooting percentage, etc.

Centenary showed up regularly in the Associated Press national Top Twenty or Top 25 polls because Jerry Byrd of the Shreveport Journal was on the voting panel in Parish's last couple of seasons and would vote the Gents No. 2 or 3 each week, giving them enough points to wind up in the Nos. 17-20 positions. (For some reason, Byrd's vote was taken away after that last season.)

Where the NCAA six-year penalty hurt Centenary most -- my opinion -- was not Parish himself, but the team not being eligible for postseason play.

It is highly unlikely that Centenary had a good enough record and enough victories over prominent opponents to have been selected for the NCAA Tournament, which then had a 32-team field (but no more than one team per conference). But the NIT (16-team field) would have been a strong possibility -- a likely spot, because of Robert's presence -- for Centenary.

The example is this: In the 1975-76 season (Robert's senior year), one of the teams chosen for the NIT was U. North Carolina-Charlotte (UNCC), featuring Cedric Maxwell and Lew Massey and coached by Lee Rose. That season Centenary beat UNCC in Shreveport and lost by one point at Charlotte in the season's next-to-last game (and Centenary missed a wide-open last-second shot).

UNCC finished second in the NIT, in Madison Square Garden (lost to Kentucky).

The next season UNCC made the NCAA Tournament, and went all the way to the Final Four (lost to eventual champion Marquette, by two points).

Maxwell would go on to be a teammate of Robert Parish with the Boston Celtics and be the MVP of the 1981 NBA Finals. Lee Rose would move from UNCC to coach at Purdue, and was back in the Final Four with a Joe Barry Carroll-led team in 1980.

(Small-world department: The Golden State Warriors made Joe Barry Carroll the No. 1 pick in the 1980 NBA Draft and their starting center, and traded their previous starter. That was ... Robert Parish, who made the most out of being sent to Boston. First year: NBA champions.)

But, of course, Parish then was still persona non grata to the NCAA, and remained that way through this last week. Yes, a 7-footer who could not be seen.

We saw him. People in Shreveport and North Louisiana saw him. People all over the country, and the world, saw him -- after he got to the NBA.

And now we can even see where he ranked -- officially -- in the NCAA statistics. Like it matters a lot now.

If the NCAA had done this anywhere from 1973 to 1976, it would have been a lot more appealing to me.

---

http://www.designatedwriters.com/daily-happen/record-book-parish-thought/

Sunday, October 22, 2017

IZ: the road from Jersey to Louisiana

(Part 3 of 4)

How did Irving Zeidman end up in Louisiana? He hopped a train ... several trains. He got off for good, in Monroe.

Born in New York City, a kid in Brooklyn and then Boonton, New Jersey (30 miles slightly northwest of NYC), he was tall early and a good high-school athlete.

He was one of three children of Jewish immigrant parents -- his father Abraham, a tailor, was from Poland; his mother, Sena (Tsena in Europe), was from the Sephardic tribe in Spain. An older sister, Betty, was born in Poland; Irving was born in 1918; a brother, Morris, followed.

Irving grew to 6-foot-4 and was a champion discus thrower and rangy, solid end in football. Wake Forest offered him a chance at college football.

Irv took a train south, to Winston-Salem, North Carolina. But it was 1940, anti-Semitism was rampant -- of course -- in Europe and too often here in the U.S., and just after he arrived at Wake, Irv heard too many "Yankee Jew" references (taunts?).

He left, after one day.

He and a buddy hopped a train going south bound for ... who knew?

IZ's daughter Susan, who lives in Frisco, Texas, said they went from town to town, begging for jobs at the train depots -- washing dishes, cleaning floors -- to earn spending money so they could keep traveling.

One train stopped in Monroe, Louisiana. And here Irv heard something that appealed: the local junior college (Northeast) was looking for football players.

Jim Malone had a powerhouse program in the late 1930s and he would coach at Northeast until the early 1950s when it became a four-year school. The now Louisiana-Monroe football stadium is named for him. When Coach Malone met young Irving, he suggested he join the team.

He played for two seasons at Northeast, well enough to earn an invitation to play at Louisiana State Normal School in Natchitoches.

But the most important part of his stay in Monroe: At school, he met Hazel Bandy, a strawberry blonde who lived with her parents in West Monroe.

They soon were in love ... for the next 35 years.

When Irving headed to Natchitoches, so did Hazel. On December 14, 1941 -- one week after Pearl Harbor -- they married.

The marriage was at the Methodist church in Natchitoches; the women's group there gave them a wedding reception. In that church, Irving did insist on one Jewish wedding ritual -- and he stomped on the glass to break it.

The Bandys thought Irving, with the sparkling personality many of us would come to know, was the right guy for their Hazel. But the interfaith marriage, as you might expect in 1941, did not sit well with the Zeidmans.

Susan: "Dad wrote a beautiful love letter to his folks telling them about Mom, and they could not help but love her."

For a honeymoon, the Zeidmans took an extremely cold bus trip to Chicago for a Methodist conference, and were fortunate to escape uninjured when the bus slid off an icy road.

In downtown Natchitoches, Susan said, Irv began his public singing career, taking part in the annual Christmas Festival.

The first child, Barbara, arrived in late in 1942. And with that, a sad story. Irving's mother had saved money to travel to see her first grandchild. She took the train from Jersey to Miami for a visit there, then on a train headed to Louisiana, she had a fatal heart attack.

Susan's daughter, Sena, is named for her great grandmother.

But Irv never got to play football for the school that a couple of years later became Northwestern State College (then University). The U.S. Army intervened, as it did with thousands of young men in those early 1940s World War II years.

So he did not have a lot of time with the baby Barbara. He left and soon learned that Hazel was expecting again.

He wound up in the personnel department of the medical corps, as a first sergeant, and in exotic locations such as South Africa and India.

Irving eventually made his living talking into a microphone, but he also was a prolific and talented writer.

Susan has copies of the extensive letters he wrote while in the Army and sent home -- interesting details of his surroundings, his moods, upbeat, with the humor he always could find, and full of -- well -- mush. "I love you, my darling," he wrote, "and am missing you. I'll love you forever." (And he did.)

In a 1943 letter, with Hazel nearing delivery, Irv was anticipating a boy he was calling Benjamin (Benjie). Soon, said Susan, he was on stage entertaining troops when he received a telegraph saying he was the father of twins -- Susan and a boy they named David.

But it wasn't all upbeat. Eventually the war -- men killing men and innocent people -- led to a mental breakdown, and a trip stateside to Brooke Army Medical Center (San Antonio) and rehabilitation.

Discharged from the service at the end of the war, life began again for Irv and the Zeidmans in Monroe.

---

The kids were young -- "we were born so close together, we were like triplets," said Susan -- and the family expanded with Danny's birth in 1946.

And Irv's career path opened with a job at KNOE Radio.

Here he became (1) a local personality, involved in many endeavors and (2) significantly, a baseball broadcaster (1951-53, Monroe Sports, Class C Cotton States League).

He was "Uncle Irv" on what was reported as a "phenomenally popular" morning radio show. Each week he featured a "happiness exchange" in which people were invited to nominate candidates for "mother of the week."

He was named assistant manager of the radio station and had a 15-minute singing program every Sunday for three years.

That might have been a warmup for his involvement there -- naturally -- in local theater productions (Abie's Irish Rose was one).

And -- ready? -- (from a Monroe newspaper article), he contributed toward the development of Little League Baseball in Monroe/West Monroe, helped in completion of a ballpark; led development of the Ouachita Parish Health Council, chairman of the Juvenile Detention Home committee, involved in the Milk Fund, the Heart Fund, the March of Dimes and the Crippled Children's board.

All that, in addition, to TV and radio sportscasts.

Little wonder he was named "Man of the Year" for 1953 by the Monroe-West Monroe Junior Chamber of Commerce, honored at a banquet.

But he wasn't there. After the end of the 1953 baseball season, Irv accepted a job at WSMB Radio in New Orleans.

So his mother-in-law accepted the award, and Irv was recognized by the Junior Chamber chapter in New Orleans, but after sending a nicely worded telegraph with thanks for the honor and his appreciation for the Monroe area.

---

One other notable opportunity developed in Monroe, said daughter Susan. Word of his acting/singing prowess reached two musical theater giants, Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein (you might have heard of them). They invited Irving to New York City for a tryout.

To pay for the trip, he did a number of fund-raising musical performances around Monroe.

It went no further, perhaps because Irv liked family life better than the uncertainty of show business.

---

The stay in New Orleans was short. The Zeidmans did not feel at home and were not satisfied with the kids' schools.

Although Irv stayed involved in sports -- he did radio play-by-play on the 1954 Sugar Bowl game (Georgia Tech 42, West Virginia 19) -- by the spring, he had accepted a job at KNOE Radio in Shreveport ... home station of the Sports.

The Zeidmans were there to stay. The kids went to Shreveport public schools; all graduated from Byrd High (Barbara in 1960, Susan and David in 1961, Danny in 1964). At the time of Irv's death, all the kids had moved on.

In Shreveport, reconnected with two of the leaders of his Monroe Sports years -- Al Mazur and Paul Manasseh.

The Monroe team had a strong Shreveport Sports connection; it was like a farm team. Several young men played first in Monroe, then in Shreveport, including future major-league pitchers Billy Muffett, Bill Tremel and Jim Willis.

In 1950-51, Mazur -- the Sports' dependable second baseman from 1946 to '49 -- was the Monroe manager; his '51 team won the Cotton States pennant. Manasseh, a Byrd High grad, was the Monroe business manager.

By 1954, Mazur had retired from baseball and begun his 33-year stay as the well-respected chief probation officer for the Caddo Parish juvenile court.

Manasseh had returned to the Sports as publicity director. In the late 1950s, he moved to Denver as publicity director for the baseball Bears (Triple-A) and the first PR man for the woeful Denver Broncos of the new American Football League. Eventually he returned to Louisiana; most notably as sports information director at LSU.

Manasseh and Zeidman not only shared Jewish backgrounds, they shared jokes and stories.

Manasseh told Bill McIntyre for his 1975 Shreveport Times column that he "recommended him [IZ] thoroughly" for the job at KENT. Jerry Byrd's Shreveport Journal column said that Manasseh often would call Zeidman -- without saying hello -- and tell him a good story, then simply hang up.

Irv, when applicable, would tell the story with a Yiddish dialect.

And Manasseh recalled being out with IZ when Irv would take over the mike at an establishment and serenade the crowd.

In 1975, when LSU played Rice in football at Shreveport's State Fair Stadium -- LSU's first game there in 16 years -- Zeidman offered to sign the pregame national anthem. That didn't work out, but Manasseh hired him to do the press box play-by-play announcements.

So we got to hear Irv on the mike again. Two months later, he died -- and as Manasseh noted then, he had just mailed Irv his $15 payment.

A poignant story involves Manasseh's daughter Marcae, the oldest of Paul's three children and the only girl.

"When my sister was a toddler, Irv would hold her and boastfully promise to sing at her wedding," recalled Jimmy Manasseh, the youngest child and now an attorney in Baton Rouge (and LSU's press-box announcer for home football games; the press box is named for his father),

Cruelly, at age 20, Marcae -- before wisdom tooth removal surgery -- had a fatal allergic reaction to the anesthetic. It was a month before her scheduled wedding.

"Irv was crushed just like our family," said Jimmy. "Instead of singing at her wedding, he sang beautifully at her funeral. It was terribly sad yet comforting to my family."

Jimmy said that "one of the only times I saw my Dad cry was when he learned of his [Irv's] death. They were very close. He always meant a lot to my Dad."

He meant a lot to many folks.

Next: If he were a rich man ...

How did Irving Zeidman end up in Louisiana? He hopped a train ... several trains. He got off for good, in Monroe.

|

| Irving, at age 13 |

He was one of three children of Jewish immigrant parents -- his father Abraham, a tailor, was from Poland; his mother, Sena (Tsena in Europe), was from the Sephardic tribe in Spain. An older sister, Betty, was born in Poland; Irving was born in 1918; a brother, Morris, followed.

Irving grew to 6-foot-4 and was a champion discus thrower and rangy, solid end in football. Wake Forest offered him a chance at college football.

Irv took a train south, to Winston-Salem, North Carolina. But it was 1940, anti-Semitism was rampant -- of course -- in Europe and too often here in the U.S., and just after he arrived at Wake, Irv heard too many "Yankee Jew" references (taunts?).

He left, after one day.

He and a buddy hopped a train going south bound for ... who knew?

IZ's daughter Susan, who lives in Frisco, Texas, said they went from town to town, begging for jobs at the train depots -- washing dishes, cleaning floors -- to earn spending money so they could keep traveling.

One train stopped in Monroe, Louisiana. And here Irv heard something that appealed: the local junior college (Northeast) was looking for football players.

Jim Malone had a powerhouse program in the late 1930s and he would coach at Northeast until the early 1950s when it became a four-year school. The now Louisiana-Monroe football stadium is named for him. When Coach Malone met young Irving, he suggested he join the team.

He played for two seasons at Northeast, well enough to earn an invitation to play at Louisiana State Normal School in Natchitoches.

|

| Irving and Hazel: the early days |

They soon were in love ... for the next 35 years.

When Irving headed to Natchitoches, so did Hazel. On December 14, 1941 -- one week after Pearl Harbor -- they married.

The marriage was at the Methodist church in Natchitoches; the women's group there gave them a wedding reception. In that church, Irving did insist on one Jewish wedding ritual -- and he stomped on the glass to break it.

The Bandys thought Irving, with the sparkling personality many of us would come to know, was the right guy for their Hazel. But the interfaith marriage, as you might expect in 1941, did not sit well with the Zeidmans.

Susan: "Dad wrote a beautiful love letter to his folks telling them about Mom, and they could not help but love her."

For a honeymoon, the Zeidmans took an extremely cold bus trip to Chicago for a Methodist conference, and were fortunate to escape uninjured when the bus slid off an icy road.

In downtown Natchitoches, Susan said, Irv began his public singing career, taking part in the annual Christmas Festival.

The first child, Barbara, arrived in late in 1942. And with that, a sad story. Irving's mother had saved money to travel to see her first grandchild. She took the train from Jersey to Miami for a visit there, then on a train headed to Louisiana, she had a fatal heart attack.

Susan's daughter, Sena, is named for her great grandmother.

|

| Irv, the World War II soldier |

So he did not have a lot of time with the baby Barbara. He left and soon learned that Hazel was expecting again.

He wound up in the personnel department of the medical corps, as a first sergeant, and in exotic locations such as South Africa and India.

Irving eventually made his living talking into a microphone, but he also was a prolific and talented writer.

Susan has copies of the extensive letters he wrote while in the Army and sent home -- interesting details of his surroundings, his moods, upbeat, with the humor he always could find, and full of -- well -- mush. "I love you, my darling," he wrote, "and am missing you. I'll love you forever." (And he did.)

In a 1943 letter, with Hazel nearing delivery, Irv was anticipating a boy he was calling Benjamin (Benjie). Soon, said Susan, he was on stage entertaining troops when he received a telegraph saying he was the father of twins -- Susan and a boy they named David.

But it wasn't all upbeat. Eventually the war -- men killing men and innocent people -- led to a mental breakdown, and a trip stateside to Brooke Army Medical Center (San Antonio) and rehabilitation.

Discharged from the service at the end of the war, life began again for Irv and the Zeidmans in Monroe.

---

The kids were young -- "we were born so close together, we were like triplets," said Susan -- and the family expanded with Danny's birth in 1946.

And Irv's career path opened with a job at KNOE Radio.

Here he became (1) a local personality, involved in many endeavors and (2) significantly, a baseball broadcaster (1951-53, Monroe Sports, Class C Cotton States League).

|

| "Uncle Irv," a popular radio man at KNOE in Monroe |

He was named assistant manager of the radio station and had a 15-minute singing program every Sunday for three years.

That might have been a warmup for his involvement there -- naturally -- in local theater productions (Abie's Irish Rose was one).

And -- ready? -- (from a Monroe newspaper article), he contributed toward the development of Little League Baseball in Monroe/West Monroe, helped in completion of a ballpark; led development of the Ouachita Parish Health Council, chairman of the Juvenile Detention Home committee, involved in the Milk Fund, the Heart Fund, the March of Dimes and the Crippled Children's board.

All that, in addition, to TV and radio sportscasts.

Little wonder he was named "Man of the Year" for 1953 by the Monroe-West Monroe Junior Chamber of Commerce, honored at a banquet.

But he wasn't there. After the end of the 1953 baseball season, Irv accepted a job at WSMB Radio in New Orleans.

So his mother-in-law accepted the award, and Irv was recognized by the Junior Chamber chapter in New Orleans, but after sending a nicely worded telegraph with thanks for the honor and his appreciation for the Monroe area.

---

One other notable opportunity developed in Monroe, said daughter Susan. Word of his acting/singing prowess reached two musical theater giants, Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein (you might have heard of them). They invited Irving to New York City for a tryout.

To pay for the trip, he did a number of fund-raising musical performances around Monroe.

It went no further, perhaps because Irv liked family life better than the uncertainty of show business.

---

The stay in New Orleans was short. The Zeidmans did not feel at home and were not satisfied with the kids' schools.

Although Irv stayed involved in sports -- he did radio play-by-play on the 1954 Sugar Bowl game (Georgia Tech 42, West Virginia 19) -- by the spring, he had accepted a job at KNOE Radio in Shreveport ... home station of the Sports.

The Zeidmans were there to stay. The kids went to Shreveport public schools; all graduated from Byrd High (Barbara in 1960, Susan and David in 1961, Danny in 1964). At the time of Irv's death, all the kids had moved on.

In Shreveport, reconnected with two of the leaders of his Monroe Sports years -- Al Mazur and Paul Manasseh.

The Monroe team had a strong Shreveport Sports connection; it was like a farm team. Several young men played first in Monroe, then in Shreveport, including future major-league pitchers Billy Muffett, Bill Tremel and Jim Willis.

In 1950-51, Mazur -- the Sports' dependable second baseman from 1946 to '49 -- was the Monroe manager; his '51 team won the Cotton States pennant. Manasseh, a Byrd High grad, was the Monroe business manager.

By 1954, Mazur had retired from baseball and begun his 33-year stay as the well-respected chief probation officer for the Caddo Parish juvenile court.

Manasseh had returned to the Sports as publicity director. In the late 1950s, he moved to Denver as publicity director for the baseball Bears (Triple-A) and the first PR man for the woeful Denver Broncos of the new American Football League. Eventually he returned to Louisiana; most notably as sports information director at LSU.

Manasseh and Zeidman not only shared Jewish backgrounds, they shared jokes and stories.

Manasseh told Bill McIntyre for his 1975 Shreveport Times column that he "recommended him [IZ] thoroughly" for the job at KENT. Jerry Byrd's Shreveport Journal column said that Manasseh often would call Zeidman -- without saying hello -- and tell him a good story, then simply hang up.

Irv, when applicable, would tell the story with a Yiddish dialect.

And Manasseh recalled being out with IZ when Irv would take over the mike at an establishment and serenade the crowd.

In 1975, when LSU played Rice in football at Shreveport's State Fair Stadium -- LSU's first game there in 16 years -- Zeidman offered to sign the pregame national anthem. That didn't work out, but Manasseh hired him to do the press box play-by-play announcements.

So we got to hear Irv on the mike again. Two months later, he died -- and as Manasseh noted then, he had just mailed Irv his $15 payment.

A poignant story involves Manasseh's daughter Marcae, the oldest of Paul's three children and the only girl.

"When my sister was a toddler, Irv would hold her and boastfully promise to sing at her wedding," recalled Jimmy Manasseh, the youngest child and now an attorney in Baton Rouge (and LSU's press-box announcer for home football games; the press box is named for his father),

Cruelly, at age 20, Marcae -- before wisdom tooth removal surgery -- had a fatal allergic reaction to the anesthetic. It was a month before her scheduled wedding.

"Irv was crushed just like our family," said Jimmy. "Instead of singing at her wedding, he sang beautifully at her funeral. It was terribly sad yet comforting to my family."

Jimmy said that "one of the only times I saw my Dad cry was when he learned of his [Irv's] death. They were very close. He always meant a lot to my Dad."

He meant a lot to many folks.

Next: If he were a rich man ...

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)