(28th in a series)

How did my Dad (Louis Van Thyn) know that his first wife had died in the Holocaust? How did he know about her parents, his in-laws, in Antwerp, or about his family back in Amsterdam?

I do not have a definite answer. Dad didn't address the subject point-blank in his 1996 USC Shoah Foundation interview, and I don't remember him talking about the specifics.

Here is what I do know: He did not return to Antwerp until more than four months after he left the concentration camp; it was six months before he went to his original home in Amsterdam.

So when the members of his family weren't there, he had to know their fate. The neighbors in both places were certain that the Nazis/Germans had taken the family members as prisoners.

In the aftermath of 4-5 horrid years of the Nazis' occupation, in the months after World War II ended, there was -- I don't believe -- no official agency to declare these people dead.

When the Nazis' files were discovered and analyzed, they had recorded much of the information about their concentration-camp prisoners -- dates they were picked up (or "arrested" ... for the crime of being Jewish, I suppose), dates they were transported to the camps, the numbers tattooed on their arms, dates and places of their death in the gas chambers or otherwise.

Imagine, though, how many details of deaths were not recorded ... the prisoners shot at random, left in the trenches they'd probably been forced to dig; those shot or hung at Nazi officers' whims; those who perished during the Death Marches when the concentration camps were abandoned near the war's end.

Once the Holocaust memorial committees were formed, including the Auschwitz Memorial committee, the available details became public.

We know now the death details of my father and mother's families; they are listed in a book (we have a copy); they are on file at the Hollandsche Schouwberg memorial in Amsterdam, on the site of the old theater where the prisoners were taken before they were transported to the camps.

There is a web site, available online: http://www.communityjoodsmonument.nl/. I have written about this previously, with links to my family's pages ... and the dates and places of their deaths.

---

But what of Dad's family in Belgium -- his wife, in-laws and his aunt/uncle/cousins with whom he first stayed when he moved to Antwerp? I did not have that information, nor did Dad have it in his files. Don't know that he ever tried to find out.

And so, a couple of months ago, I searched online for the Holocaust memorial in Belgium, similar to the one in Amsterdam.

I found a link to the Kazerne Dossin, a memorial, museum and documentation center in Mechelen -- on the transit-camp site where many of the Jews taken prisoner by the Nazis were first sent. Among those prisoners: Louis Van Thyn. (I've written about that in this series.)

So I wrote asking for information on Dad and on Estella Halverstad (his first wife), anyone named Halverstad (hopefully, her parents), and on the Scholte family (Dad's aunt, uncle and cousins).

Thanks to Dorien Styven, who replied with (1) information on the people, and (2) digital copies of the documents in the Kazerne Dossin files. This includes -- most pertinent to me -- the files on Dad and Estella.

This included their entries in the Jewish Register of Belgium, a must forced by the Nazis from December 1940 onward; their membership cards in the Jewish Association of Belgium, a requirement for Jewish families living in the country in the spring of 1942 onward; and the Kazerne Dossin transportation lists (to the concentration camps).

Here is the information pertaining to my Dad and his cousins:

"In June and July 1942, the Nazis claimed 2,250 Jewish men in Belgium and sent them to the north of France, where they worked as slave labourers for Organisation Todt, the German enterprise responsible for the built (cq) of the Atlantic wall. Among these workers were Levie Van Thyn and his cousins Jonas and Joseph Scholte. In October the Nazis noticed that they would not reach their Belgian deportation quota, so they sent a few of the Organisation Todt workers to the Dossin barracks in Belgium. Levie Van Thyn and Jonas Scholte arrived there on 21 October 1942, Joseph Scholte on 23 October 1942. Levin Van Thyn, and Jonas and Joseph Scholte became person 180, 181 and 277 on the transport XV. This train left Dossin on 24 October 1942 and arrived at Auschwitz-Bierkenau on 26 October 1942."

In another paragraph:

"Levie Van Thyn was selected to perform forced labour. The number 70726 was tattooed on his arm. Further information concerning his survival is unknown to us. We can only confirm that he was repatriated in 1945. Any details concerning his history are most welcome."

I assure you that I have the details on his history. And I have given them to the Kazerne Dossin.

---

In the paragraph immediately following the information on Dad, it details one of his cousin's history:

"Joseph Scholte was also selected to perform forced labour upon arrival in Auschwitz-Birkenau. The number 70801 was tattooed on his arm. Joseph survived his captivity in Auschwitz and Jawisowitz, and the death marches to Buchenwald in 1945. He was liberated in Crawinkel on 8 April 1945 by the American Army and was repatriated on 2 June 1945."

We knew him as "Joopie," and I am proud to say that I remember him from my childhood in Amsterdam.

Before and after the war, he was a diamond cutter -- he stuck with it when Dad didn't -- and he was perhaps my Dad's greatest friend for the next 45-50 years, and I will have more on his family, his life and their friendship in a future chapter.

I will tell you this now: He is one of the great heroes of my life.

---

The Kazerne Dossin information on his older brother, Jonas, did not have a happy ending. It said this:

"Unfortunately, we don’t know what happened to Jonas Scholte upon arrival in the camp because we didn’t find a death certificate or a document with a tattoo number on his name. However, this does not necessarily mean that he was sent to the gas chambers immediately since the Nazis destroyed large parts of the Auschwitz archives in 1945. We can therefore only confirm that Jonas Scholte died after deportation, but we can’t add any information on the date, place or circumstances of his death."

But what of Estella, and her parents -- Abraham Halverstad (a diamond cutter) and Sara Verdoner -- and her maternal grandmother, Judie Boekman (who was 77 then)?

"Estella Halverstad, wife of Levie Van Thyn, presented herself voluntarily at the Dossin barracks on 26 August 1942. She had received an Arbeitseinsatzbefehl, a Nazi letter summoning her for forced labour in the east. At the camp administration she was registered as person 793 on the deportation list of transport VI. This train left Mechelen on 29 august 1942 and arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau on 31 August 1942. ..."

The information also lists the arrest and transportation details for her father, mother and grandmother.

But in each case, including Estella, the description ends with ... "Unfortunately, we don't know what happened to (name) upon arrival in camp ... we can only therefore confirm that (name) died after deportation ..."

That's the confirmation that -- perhaps -- my Dad never saw. And that's OK.

Next: Finding the survivors

I do not have a definite answer. Dad didn't address the subject point-blank in his 1996 USC Shoah Foundation interview, and I don't remember him talking about the specifics.

Here is what I do know: He did not return to Antwerp until more than four months after he left the concentration camp; it was six months before he went to his original home in Amsterdam.

So when the members of his family weren't there, he had to know their fate. The neighbors in both places were certain that the Nazis/Germans had taken the family members as prisoners.

In the aftermath of 4-5 horrid years of the Nazis' occupation, in the months after World War II ended, there was -- I don't believe -- no official agency to declare these people dead.

When the Nazis' files were discovered and analyzed, they had recorded much of the information about their concentration-camp prisoners -- dates they were picked up (or "arrested" ... for the crime of being Jewish, I suppose), dates they were transported to the camps, the numbers tattooed on their arms, dates and places of their death in the gas chambers or otherwise.

Imagine, though, how many details of deaths were not recorded ... the prisoners shot at random, left in the trenches they'd probably been forced to dig; those shot or hung at Nazi officers' whims; those who perished during the Death Marches when the concentration camps were abandoned near the war's end.

|

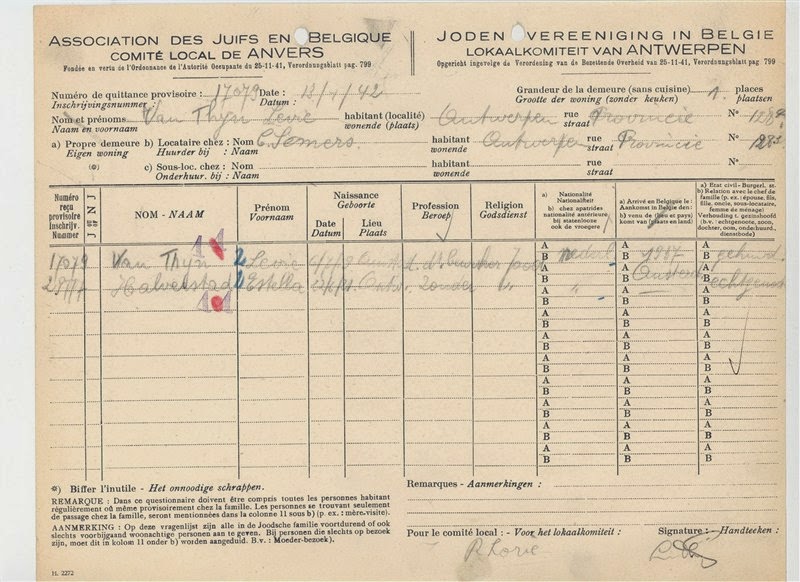

| My Dad's registration card with the Jewish Register of Belgium, 1940 |

Once the Holocaust memorial committees were formed, including the Auschwitz Memorial committee, the available details became public.

We know now the death details of my father and mother's families; they are listed in a book (we have a copy); they are on file at the Hollandsche Schouwberg memorial in Amsterdam, on the site of the old theater where the prisoners were taken before they were transported to the camps.

There is a web site, available online: http://www.communityjoodsmonument.nl/. I have written about this previously, with links to my family's pages ... and the dates and places of their deaths.

---

But what of Dad's family in Belgium -- his wife, in-laws and his aunt/uncle/cousins with whom he first stayed when he moved to Antwerp? I did not have that information, nor did Dad have it in his files. Don't know that he ever tried to find out.

|

| Dad and Estella's registration card with the Jewish Association of Belgium, spring 1942 |

I found a link to the Kazerne Dossin, a memorial, museum and documentation center in Mechelen -- on the transit-camp site where many of the Jews taken prisoner by the Nazis were first sent. Among those prisoners: Louis Van Thyn. (I've written about that in this series.)

So I wrote asking for information on Dad and on Estella Halverstad (his first wife), anyone named Halverstad (hopefully, her parents), and on the Scholte family (Dad's aunt, uncle and cousins).

Thanks to Dorien Styven, who replied with (1) information on the people, and (2) digital copies of the documents in the Kazerne Dossin files. This includes -- most pertinent to me -- the files on Dad and Estella.

This included their entries in the Jewish Register of Belgium, a must forced by the Nazis from December 1940 onward; their membership cards in the Jewish Association of Belgium, a requirement for Jewish families living in the country in the spring of 1942 onward; and the Kazerne Dossin transportation lists (to the concentration camps).

Here is the information pertaining to my Dad and his cousins:

"In June and July 1942, the Nazis claimed 2,250 Jewish men in Belgium and sent them to the north of France, where they worked as slave labourers for Organisation Todt, the German enterprise responsible for the built (cq) of the Atlantic wall. Among these workers were Levie Van Thyn and his cousins Jonas and Joseph Scholte. In October the Nazis noticed that they would not reach their Belgian deportation quota, so they sent a few of the Organisation Todt workers to the Dossin barracks in Belgium. Levie Van Thyn and Jonas Scholte arrived there on 21 October 1942, Joseph Scholte on 23 October 1942. Levin Van Thyn, and Jonas and Joseph Scholte became person 180, 181 and 277 on the transport XV. This train left Dossin on 24 October 1942 and arrived at Auschwitz-Bierkenau on 26 October 1942."

In another paragraph:

"Levie Van Thyn was selected to perform forced labour. The number 70726 was tattooed on his arm. Further information concerning his survival is unknown to us. We can only confirm that he was repatriated in 1945. Any details concerning his history are most welcome."

I assure you that I have the details on his history. And I have given them to the Kazerne Dossin.

---

In the paragraph immediately following the information on Dad, it details one of his cousin's history:

"Joseph Scholte was also selected to perform forced labour upon arrival in Auschwitz-Birkenau. The number 70801 was tattooed on his arm. Joseph survived his captivity in Auschwitz and Jawisowitz, and the death marches to Buchenwald in 1945. He was liberated in Crawinkel on 8 April 1945 by the American Army and was repatriated on 2 June 1945."

We knew him as "Joopie," and I am proud to say that I remember him from my childhood in Amsterdam.

Before and after the war, he was a diamond cutter -- he stuck with it when Dad didn't -- and he was perhaps my Dad's greatest friend for the next 45-50 years, and I will have more on his family, his life and their friendship in a future chapter.

I will tell you this now: He is one of the great heroes of my life.

---

The Kazerne Dossin information on his older brother, Jonas, did not have a happy ending. It said this:

"Unfortunately, we don’t know what happened to Jonas Scholte upon arrival in the camp because we didn’t find a death certificate or a document with a tattoo number on his name. However, this does not necessarily mean that he was sent to the gas chambers immediately since the Nazis destroyed large parts of the Auschwitz archives in 1945. We can therefore only confirm that Jonas Scholte died after deportation, but we can’t add any information on the date, place or circumstances of his death."

But what of Estella, and her parents -- Abraham Halverstad (a diamond cutter) and Sara Verdoner -- and her maternal grandmother, Judie Boekman (who was 77 then)?

"Estella Halverstad, wife of Levie Van Thyn, presented herself voluntarily at the Dossin barracks on 26 August 1942. She had received an Arbeitseinsatzbefehl, a Nazi letter summoning her for forced labour in the east. At the camp administration she was registered as person 793 on the deportation list of transport VI. This train left Mechelen on 29 august 1942 and arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau on 31 August 1942. ..."

The information also lists the arrest and transportation details for her father, mother and grandmother.

But in each case, including Estella, the description ends with ... "Unfortunately, we don't know what happened to (name) upon arrival in camp ... we can only therefore confirm that (name) died after deportation ..."

That's the confirmation that -- perhaps -- my Dad never saw. And that's OK.

Next: Finding the survivors