|

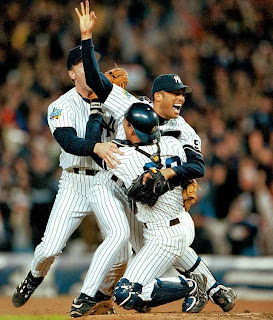

| Two of five: Mariano Rivera and the Yankees celebrate World Series championships |

|

| photos from sportsillustrated.cnn.com |

More than a thousand times over 19 baseball seasons I have watched a New York Yankees game in person or on television or followed on computer and said, "C'mon, Mo, get this guy out."

Like millions of Yankees fans -- yes, millions -- I feel blessed that he pitched for our team.

Even non-Yankees fans -- I've been told there are a few out there -- can appreciate the greatness he has brought to the game.

I don't like "greatest" labels, as I've written previously, but in Mariano's case, it works. He's the greatest closer in baseball history, we can all agree.

It is -- as one of my favorite songs says -- time to say good-bye, to Mo and to Andy Pettitte, the other retiring Yankees pitcher. Sunday's game in Houston will be the last of their careers, whether they pitch or not.

Soon, too -- maybe next season, or maybe even before that -- it will be the end of Derek Jeter's playing career, too. Rivera, Pettitte, Jeter ... three in the long line of Yankees' all-timers, all with five World Series titles.

All have played with brilliance and confidence and talent, and with dignity, not showing off or showing up opponents or umpires, all clubhouse leaders, all media favorites.

Rivera and Jeter are Baseball Hall of Fame locks, first-time ballot selections.

Pettitte's Hall credentials aren't as certain; his numbers are very good; he won many big games, but he admitted using human growth hormones twice in 2004 when he was injured, and that might keep him out of the Hall.

---

---

With Rivera, it's more than the 90 victories (61 losses), his 8-1 postseason record and four World Series closeouts, the 694 saves (a record 652 regular season, 42 postseason), the 1,211 pitching appearances, 13 All-Star Game selections, the symbolism of his being the last MLB player to wear jersey No. 42.

It's his class.

You can say the same about Jeter and, to a slightly lesser extent, Pettitte. But this piece is about Rivera, about this final season.

In last week's Sports Illustrated cover story, "Exit Sandman," this quote from Joe Torre was so noteworthy: "Probably not since [Sandy] Koufax have we seen anyone leave the game with so much respect."

Torre played against Koufax and was Rivera's manager for 12 seasons, four of them ending with World Series titles.

The only thing wrong with Koufax, in my view, was he didn't pitch for the Yankees. He is my favorite non-Yankees player ever.

Of course, I have many Yankees favorites. One was Sparky Lyle, the closer for much of the 1970s who was eccentric, and fearless. Sure, Reggie hit those home runs in the final game of the 1977 World Series, but without Sparky's work that season, no way the Yankees even reach the World Series. He was Cy Young that year.

Like Lyle's slider, Rivera did it mostly with one pitch -- that cut fastball which broke so many bats and left so many batters perplexed with its late-breaking movement.

But what I loved most about Rivera -- other than the confidence he gave us Yankees fans -- was that he rarely showed any emotion, he just did his job. If he closed out a game, he might make a small fist pump. If he gave up a big home run or lost a game, you might see a grimace. Almost always, it was strictly business.

However, I saw a video a few years ago in which Mo is screaming for several moments at someone in the Yankees' bullpen area. Don't know what that was about, never saw an explanation. What it did show me -- as if I ever doubted it -- was that there was some fire beneath that placid expression.

---

---

My favorite Mo moments, though, are when he did show emotion -- the pennant- or Series-clinching celebrations. Especially the 2003 ALCS when, as Aaron Boone rounded the bases after his pennant-winning home run against the Red Sox, Mariano ran to the mound and fell on his hands and knees, bent over, crying. It was his greatest pitching performance -- three innings of shutout relief in a tense, all-on-the-line game.

And it wasn't all good; he dealt with big losses, with injury, and with tragedy. It proved he was as human as the rest of us.

In 2004, just before the American League Championship Series, two relatives were electrocuted while cleaning the pool at Rivera's home in Panama. He flew there to attend to matters, then returned to his team.

His three postseason blown saves were huge -- Cleveland in Game 4, 1997 (his first year as closer); Boston in Game 4, 2004 (starting the Red Sox's fabled comeback from an 0-3 series deficit vs. the Yankees and triggering their long-awaited World Series championship -- no more "1918"; and the bottom-of-the-ninth Game 7 vs. Arizona in the 2001 World Series.

He had elbow surgery in 1992 before his career really got started, when few knew who he was, and the wrecked right knee (torn ACL) on the warning track in Kansas City during batting practice in May 2012. He had announced that 2012 would be his final season, but he didn't want his career to end like that.

So he came back, rehabbed the knee, and he's been darned good this season (44 saves) at age 43. It's been a miserable season for the Yankees -- even Mo had seven blown saves, his most since 2001 -- but it would have been worse without him.

He never, win or lose, skipped out facing the media after games.

|

| The young Mariano Rivera, in 1996 with catcher Joe Girardi, his manager in his final six seasons (blogsport.com) |

The farewell tour has been unique. At each stop the Yankees made, the opposing team has honored Rivera with a short ceremony and gifts, such as donations to his foundation.

One touching ceremony was the one a couple of weeks ago in Boston -- at Fenway Park, where the Yankees aren't exactly loved.

But making the farewell tour even more special is that also at each stop -- and this was Mariano's idea -- he took 30-45 minutes and sat down to meet with longtime ballpark employees or fans just to thank them. To read the stories, those people all came away impressed and thrilled at how genuine, how humble Mo is.

The greatest moments, though, have come this past week at Yankee Stadium -- last Sunday when his Yankees number was retired, so many from the recent dynasty years returned and the Yankees gave him about as many gifts as he has saves, and again Thursday night when he pitched for the last time in pinstripes.

---

For the past 10 years, Rivera has been the only MLB player to wear No. 42 every day. The number was retired by MLB on April 15, 1997, to honor Jackie Robinson, who 50 years earlier to the day had broken the major leagues' color barrier. At that time, 13 players were wearing No. 42 and the "grandfather" clause allowed them to keep doing so until they chose not to or left the game.

Now, only on April 15 each year, everyone in uniform in MLB wears No. 42. We all think of Robinson that day, but Yankees fans will think of Rivera, too.

Growing up in Panama, the son of a fisherman, Rivera did not know much about Robinson. But he learned, he studied the man and his history, and he honored the wearing of No. 42. He came to represent the ideals that Jackie brought to the game and to society.

But Jackie, after that first MLB season when he quietly absorbed the abuse as the first black in the game, was a lightning-rod player, not beloved by many opponents.

Rivera has been beloved, certainly respected, by just about everyone.

I wish he could pitch forever and Jeter could play shortstop. But time doesn't wait on athletes, and it's time to move on.

I've never been to Cooperstown, to the Baseball Hall of Fame, but several years ago I told my wife that I wanted to go when Mariano and Derek are inducted. So, hopefully, we'll be there in late summer 2019 when it's Mo's day. Derek will mean a return trip a year or two later.

It's not easy to say good-bye. But it is easy to say thanks to our No. 42, the great Mariano.

|

| One final championship: 2009 |