|

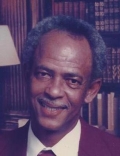

| Clifford Pennywell |

When I saw that Clifford had passed away, I had a feeling of regret. He was an interesting guy, a guy I wish I had gone back and visited, just to touch base and rehash the years. Because, even though our relationship was fine, I always felt I hadn't know him well enough.

How many times do we wish for that one more conversation? I could give you a quick list of a hundred people that would fit that category? Anyway, more about Pennywell in a moment.

The integration of schools in Caddo and Bossier Parishes -- court-ordered, of course -- in January 1970 was a difficult time for everyone -- administration, faculties, students, the public, even the media.

It began with the shifting of administrators and faculty members, including coaching staffs. Whites were sent to all-black schools; blacks were sent to all-white (with a few exceptions) schools.

Longtime coaching staffs were broken up. No one was very happy. The ones sent to other schools didn't want to be there; the people remaining at those schools didn't want them there.

And that was only the preliminary steps. Beginning with the next school year in the fall, students were shifted. Previous all-black high schools -- such as Union, Valencia, Eden Gardens, Walnut Hill, Charlotte Mitchell (Bossier) -- were closed; those students were integrated into previous all-white schools such as Woodlawn, Southwood, Captain Shreve, Byrd, Fair Park and Northwood.

Some all-black high schools -- Booker T. Washington, Bethune and Linear -- remained open. But the LIALO, the athletics association for blacks, folded into the LHSAA.

Schools in Shreveport-Bossier -- and other places -- changed for good; so did athletics. For the better? In some ways, yes; in some ways, probably not. It's an individual judgment. Certainly, I'd say the quality of athletes was as good as it'd ever been. Attendance and public interest weren't.

In Caddo Parish, and Bossier, head coaches in football and basketball remained intact wherever possible. But the men who had been head coaches at the all-black schools that closed were forced to move, most of them to assistant-coach positions, with the promise of first shots at head coaching jobs that came open.

Which brings me back to Clifford Pennywell, who of all the coaches forced to move might've gotten the most unfortunate deal for one major reason.

Pennywell was Robert Parish's first high school basketball coach. But not his last.

In Parish's freshman and sophomore years, the still raw but already 7-foot center led Union High -- with Pennywell as coach -- to the LIALO state semifinals. But when Parish and the rest of the Union students were sent to all-white schools -- most of them to nearby Woodlawn -- Pennywell didn't go with them.

Woodlawn already had a very successful coach, Ken Ivy, who had taken his 1968-69 team to the Class AAA state championship (a team that included one black starter, an All-State point guard named Melvin Russell, who had come to Woodlawn from Union on a "freedom of choice," or minority-to-majority, transfer allowable at that time.)

Pennywell, meanwhile, was able to continue as a head coach when there was an opening at Booker T. Washington, and he was also the athletic director there. And for the next decade, BTW was usually one tough basketball team to face. Pennywell knew what he was doing.

---

That first school year of integration, 1969-70, was also my first year as a fulltime sportswriter at The Shreveport Times. We had an all-white sports staff and we rarely, if ever, covered the LIALO school games.

We left that to a correspondent named Andrew Harris, sports editor of the Shreveport Sun, which served the black public. He was a decent writer and reliable, friendly guy who, if things had been different, could have been on our sports staff.

The next school year, when the all-black schools merged into the LHSAA and our realm, I was beginning to take over direction of the prep coverage. I went to each Caddo-Bossier school -- more than a dozen -- before that football season for a preview and to meet the coaching staffs, to let them know we were interested.

Here's what I found: Coaches were coaches, people were people.

Many of the black coaches whom I hadn't met before were classy and capable and friendly. Some proved not to be as capable, and left the feeling they didn't trust you. Some were easily accessible; some were extremely difficult to reach, even by phone.

Some consistently had winning teams and lasted a long time in the job. Some did not win, and left coaching in a short time. Some did not win, but were great with the kids, dealt well with people, and lasted a long time because the Caddo Parish School Board did not emphasize winning.

Some were bitter about their schools being closed and their positions taken away, and that was understandable.

Some appreciated what was written about them and their teams; most did not say much in that regard. (Same as white coaches, I must add).

One coach, a year or two after leaving coaching, was flat-out ugly to me verbally one day, accusing me of racism.

Another, a successful basketball coach, screamed at me one day in his team's locker room after a game, telling me to "get out and leave my kids alone." The story was this: A couple of times driving away from the school, I had seen three of his top players walking home after a game, asked if they needed a ride, and gave it to them. I'm not sure what he thought I was doing other than trying to be helpful.

Another basketball coach, a popular guy I really liked, ordered me out of his gym during practice one day because he was mad that his team had dropped in The Times' area poll. He blamed me for that; actually, I was only one of about 10 voters in the poll.

A baseball coach, on the phone calling in statistics, point-blank accused me of being prejudiced against his team one day.

But mostly there were friendships made and a mutual respect, and I found so many good guys who wanted to coach, who loved the kids, and who wanted to win.

---

Clifford Pennywell was an "old-school" guy. He had grown up in Shreveport when being a black person meant tough times. He had attended the Colored Central school which preceded BTW's opening on Milam Street in 1949. He began coaching in 1956 and was comfortable in his setting at Union.

So moving to BTW in 1970, staying in an all-black setting, was probably OK with him. Still, it had to be bittersweet for him to see Parish and some of the other kids he had coached at Union go to Woodlawn and have back-to-back seasons of 35-2 and 36-2, state runner-up and state championship teams. And to have his BTW teams play against Parish and Woodlawn.

Clifford was, I know, tough on his players, worked them hard. A friend told me he stressed being at practice and being on time and, if the kids were late or misbehaving, "he'd lay the wood on them" (paddled them).

He was one of the great whistlers I've seen in coaching (Louisiana Tech football assistant/baseball coach Pat "Gravy" Patterson was the other). When Pennywell whistled in the cozy BTW gym, you could hear it on nearby Milam Street. It caught everyone's attention, but especially his players.

BTW had some very competitive teams that made the playoffs and one wonderful guard named Billy Burton, who was our Times co-Player of the Year with Airline's Mike McConathy in 1973 because I didn't want to pick one over the other.

But Clifford was a hard guy to figure. Many people felt he was arrogant, or haughty -- and I could see why. He was sure of himself, but also pretty guarded. To me, he was like the Wizard of Oz; there was something behind the Pennywell curtain you weren't going to see.

He wasn't expansive with answers to questions, but he didn't make excuses for his team, wasn't all that critical of referees (but there would be veiled hints) and when he was done with an interview or a conversation, he sometimes just turned and walked off without a good-bye. He had, as a friend noted, "an attitude."

I know, though, that he liked me because he would joke with people he liked, and he'd often have a wisecrack for me when I'd cover a game involving BTW (I did more than a couple of "Soul Bowl" BTW-Green Oaks football games.)

I do remember he never complained about coverage, and that extended to the coverage of his son, Carlos, who -- because the Pennywells lived across town from BTW -- played for Captain Shreve.

Carlos was one of the great all-around athletes in Shreveport-Bossier history -- a football/basketball/baseball star, the best player (an explosive wide receiver) on Shreve's 1973 state football championship team, and also a sometimes demonstrative talent not well-liked by opponents. (He went on to star in football at Grambling, then spent four seasons -- 1978-81 -- with the New England Patriots, and probably should have been in the NFL longer than that.)

Again, as with Parish, it must've been tough for Coach Pennywell to see his own son play (and beat) the teams he coached.

One of his coaching contemporaries talked about how organized he was, how -- as a P.E. teacher and coach -- he held to the values he had learned at Grambling under Prez Jones and Eddie Robinson, and how much of a role model he was for younger black coaches, how he worked to get his players college opportunities. And, yes, he didn't socialize or mix much with other coaches; thus, the reputation for being his own man.

I learned this week that Clifford had been in a nursing home for some eight years, and I'm so sorry to hear that. He was, above all, a good family man. And to me, he was a symbol of a difficult but important transition in Shreveport-Bossier athletics.

From Lonnie Dunn, Shreveport: I went to Union during the "crossover" in 1970 as an assistant principal and spent from February until the end of the school year before the senior high transitioned to Woodlawn in the 70-71 school year. Got to spend some real quality time with Coach Pennywell. He did more to keep the lid from blowing off than anyone else, including the principal. He was a quality guy and I had a lot of respect for him. We spent a lot of time working together to keep Union Junior-Senior High School a safe place for all involved!

ReplyDelete